The Wizarding World's Tools of Economic Magic: 'LTV'/'Value', 'Consolidation'/'Growth', and 'Rules'/'Law'

So as we turn to what it is that enables such behavior, and what it is that

they feel gives

them the authority to behave as

their hearts desire, we see that it requires detaching you from reality and subduing you to its economic orders, through the manipulation of three key fixtures:

- LTV (Labor Theory of Value),

- (refuting) Say's Law,

- Law.

#1 - LTV involves making use of an early and partial error in defining observations, which has subsequently been reinforced across time into an evasive lie, which is what it is. It's not a thing of value, it's a scheme for enslaving the values of others. As you might imagine, my xTwitterers disagree with me on this, and think those who're 'liberty minded', need to do better. Indeed.

xTwitter'rs tell me:

"Ambrosius Macrobius @weremight

Arguing against LTV is a mug's game. Jes' Sayin'. Liberty minded individuals need to do better."

We can look to LTV's origin as coming from a selective reading of John Locke, which was furthered in some ways by Adam Smith's pioneering effort to identify what Value is in the context of political economy, and from that end of history it was an understandable, if crude effort, but from this end of history, it doesn't stand up to thinking past two or three questions deep. Not that proponents of LTV can't make its calculations 'add up' by throwing one new epicycle after another upon it (notice the magicians wand waving of Inflation! Interest Rates!) - that hasn't changed much from Ptolemy's day to ours - but what it cannot stand up to, is a series of

non-economic questions, which is why they aren't raised or acknowledged.

The real value that LTV has for the field of 'economics' today, is that it enables the dismissal and even disparagement of the individual's right to put thought and effort into producing value, through its claim that Value is ultimately reduceable to a collective muscular effort of "

socially necessary labour time", as Karl Marx termed it. Whether or not most supporters of LTV realize it, Marx clearly saw what value LTV would have for

his deliberate assaults upon every aspect of the West, and ever since his efforts it has played an essential role in utilizing all of the dazzling machinery of economic indexes & measurements that 'economic thinkers', from the 'Classical Liberal's on down to today, have used in diverting attention away from the void that LTV injects into popular thinking.

This is something that shouldn't be passed over lightly:

Marx & Engles's purpose for advancing communism was always that communists should, in their words:

'... openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions....'

The same destructive purpose that drove Marx in writing the Communist Manifesto, was the same malevolent sentiment that drove his poetry, plays, and other writings, and is embodied in his favorite quotation from his favorite play, "Dr. Faust", which everyone who knew Marx brought up when recalling him, where the demon 'Mephistopholes' says:

"Everything that exists deserves to perish"

That's not the hallmark of a person who entered into

anything for productive purposes. Marx didn't turn from writing the Communist Manifesto, to injecting 'Das Kapital' into 'Economics', in order to explain a theory of value best suited to improving the economy of any nation, but because he saw 'Economics' as the most effective means of bringing utter destruction to the Greco/Roman-Judeo/Christian West.

Thinking that Marx settled upon LTV (Labor Theory of Value) because it was 'true', and would be beneficial in improving people's understanding of markets... is less foolishly naive, than dangerously negligent.

The calculative machinations that fill

this paper:

"...The alleged refutation of the labour theory of value was an integral part of the marginalist attack against Classical and Marxist analysis. However, statistical analysis of price-value relationships made possible by the data available since the later 20 th century suggest considerable empirical strength of the labour theory of value..."

, are dazzling, but they are just that. Machinations. And like Ptolemy, though without his innocence, they're able to make their numbers match with what we see from our position on the surface of the economy, while at the same time concealing those aspects of reality that threaten their views.

But just as no matter how well Ptolemy's epicycles got his numbers to add up, I'm not going to be buying that either Mars or the Sun are revolving around the Earth, I'm also not going to go along with the pretense that LTV is a legitimate 'economic tool' for monitoring, evaluating, and ultimately

justifying the forceful governing of society through.

I'm not opposed to LTV because I'm concerned that its numbers don't add up - though I'd be surprised if their various epicycles didn't have them adding up impressively well - even if their fellow economists of nominally opposing camps (see

here and

here) routinely counter them - I dismiss it out of hand as an invalid concept, because of the more important reality which it

participates in evading.

See if you can catch a glimpse of what I'm referring to here, in this explanation from

a socialist supporter of LTV (which, BTW, gives a more accurate summary of Marx's positions than most of his economic opponents or supporters do):

"...Moreover, it is unquestionably the case that Marx’s approach to the subject has made an impact even on mainstream economics itself. For example, his notion of the real price of labour power being the time it takes for an average worker to obtain the money to purchase a given basket of goods is widely seen to be a particularly useful measure of comparative living standards between countries. Similarly, his argument that the real price of commodities (as measured by their labour content) will tend to fall as a result of mechanisation. Progressively replacing living labour does seem to have been borne out by the facts. Technological innovation has indeed brought about a remarkable reduction in the real price of many commodities...."[emphasis mine]

What I'm drawing your attention to here is less an issue of converting dollars to pesos, than to how the wording reveals a glimpse of what's being concealed.

The contextual differences in

'comparative living standards' experienced with, "

...a given basket of goods is widely seen to be a particularly useful measure of comparative living standards between countries...", are squeezed out consideration. What's not compared - what is left unseen - are such conditions as how a worker is

able to work (by choice or forced, freely hired, or unionized), was that 'given basket of goods' filled by the worker's selections at a market that had some say over what they were offering, or were those the only goods supplied to them and so him, which excludes the most important factor of comparing markets out of the equation?

What that reduces the 'comparison' to, is a purely material measurement of quantities of things 'between countries', which are then calculated for

as if they represented only a mere matter of converting dollars to pesos.

That is the wizardry of economics in action.

It's up to us to poke at what we can glimpse is being left out of these claims, to question how it is that one country has more valuable "

socially necessary labour time", than the other? Why are there

any differences in standards? Does the musculature of the people of one country, differ so much from the muscles of those of the country they're being compared to? What guides those muscles, or is it muscle alone that powers '

a result of mechanization', or of '

Technological innovation'? Where do those 'powers' come from?

I'm not asking those questions to get their answers, but to indicate what they won't acknowledge, or ask, but only explain their way around. Take for instance the LTV practice of FDR's 'workers' programs that paid one set of ditch diggers to dig a trench, and another to then fill it back in, which, after all, was rewarding them for performing a "

socially necessary labour time" - the fact that nothing of VALUE was created by that, is ignored, and argued away by various statistically impressive calculations for those ends justifying their means.

You need not doubt that they

do have 'answers' of their own -

lots of them - but their answers to such questions typically involve or depend upon the massaging of issues of Supply & Demand, Class warfare and considerations of Oppressor/Oppressed dynamics into their calculations. The sheer quantity of such 'answers' enables them to turn a blind eye to any honest (what is necessary for 'honesty'?) consideration of LTV's nature, until what they'll admit is 'seen', has been transformed into an inert 2D material thing that can be safely manipulated into the economic machinery of

'differences in standards'.

If you can avoid being diverted into the usual issues of Supply & Demand and class consciousness, and instead poke around a bit deeper into the philosophic nature of the 'economic' front, you'll soon find one or more equivocations such as those involved in LTV.

A ready example of there being far more than "socially necessary labour time" involved in determining values, is readily at hand in any movie you might choose to watch, decide what you think of it, and then watch the credits roll.

Those several minutes' worth of credits that we now see scrolling by at the end of any big budget movie, comprise those who were determined to be of value by a decision maker (individual or corporate), to provide products & services that were deemed necessary to get the movie made. What is seen in the credits, are what reflect the producers view of what they'd judged to be worth paying for.

- What is unseen, though assumed, in the credits, is how each of those credited for their services, had negotiated with the producers for the value of what they would or would not include in their services that were listed in the credits, and clearly an agreement over their value to the production was successfully made.

- What goes unseen, are those choices and services that were passed over, either by those potential providers who decided that their services were worth more than the producers were offering, or because the movie's producers decided that their services were not valuable enough to the production to be secured.

All of those factors and values that were negotiated, went into determining the

cost (actual, opportunity cost, etc.,) of making that movie you're watching the credits of. But although each of those services gave value to the producer and (presumably) earned a profit for themselves, neither their nor the producer's efforts determine even the

monetary value of that movie.

How the monetary value of a movie is ultimately determined, is by what is or isn't successfully negotiated between movie goers such as yourself - customers - and what the theater box-offices asked for the privilege of viewing it. The results of

all of those negotiations added together, go into determining whether that big budget movie is shown to have the monetary value of a blockbuster success, or of a box-office bomb. And of course there are many movies that bombed at the box-office, that many people have spent uncounted hours watching over and over again because, in their judgement, it adds value to their lives - '

It's a wonderful life!' comes to mind, considered a box office failure when released, has steadily grown in value since then to a great number of people worldwide.

All of that involves 'value' being determined and used in several different contexts - as it should be - and

none of those values add up to

'socially necessary labor time'.

What the 'error'/judo-flip lies in, and relies upon, is you not engaging your judgement, so that LTV can maintain the pretense that

'socially necessary labor time' is the 'heart and soul' of Value.

Bastiat clarified the issues involved in this, in these two essays from 150 years ago, from '

of Value':

"...Hitherto the principle of Value has been sought for in one of those circumstances which augment or which diminish it, materiality, durableness, utility, scarcity, labour, difficulty of acquisition, judgment, etc., and hence a false direction has been given to the science from the beginning; for the accident which modifies the phenomenon is not the phenomenon itself. Moreover, each author has constituted himself the sponsor, so to speak, of some special circumstance which he thinks preponderates,—the constant result of generalizing; for all is in all, and there is nothing which we cannot comprehend under a term by means of extending its sense. Thus the principle of value, according to Adam Smith, resides in materiality and durability; according to Jean Baptiste Say, in utility; according to Ricardo, in labour; according to Senior, in rarity; according to Storch, in the judgment we form, etc.

The consequence has been what might have been expected. These authors have unwittingly injured the authority and dignity of the science by appearing to contradict each other; while in reality each is right, as from his own point of view. Besides, they have involved the first principles of Political Economy in a labyrinth of inextricable difficulties; for the same words, as used by these authors, no longer represent the same ideas; and, moreover, although a circumstance may be proclaimed fundamental, other circumstances stand out too prominently to be neglected, and definitions are thus constantly enlarged..."

, and '

Exchange':

"...From this I conclude that value (as we shall afterwards more fully explain) does not reside in these substances themselves, but in the effort which intervenes in order to modify them, and which exchange brings into comparison with other analogous efforts. This is the reason why value is simply the appreciation of services exchanged, whether a material commodity does or does not intervene. As regards the notion of value, it is a matter of perfect indifference whether I render to another a direct service, as, for example, in performing for him a surgical operation, or an indirect service, in preparing for him a curative substance. In this last case the utility is in the substance, but the value is in the service, in the effort, intellectual and muscular, made by one man for the benefit of another. It is by a pure metonymy that we attribute value to the material substance itself, and here, as on many other occasions, metaphor leads science astray..."

, and as Bastiat concludes later in the same essay:

"I say, then, Value is the relation of two services exchanged."

And if I might venture just a step beyond Bastiat's argument, I'll point out that the root of what is exchanged, grows from a person's thoughts being put into action, first in the formation of Property, and then as a value that is created from the mutually agreed upon actions from all parties to their exchange.

It is thought put into action, that is the determiner of what property you have in the goods or services you produce. What is produced, is produced for the purposes of exchanging it for other goods & services, because in the context of that exchange, you place more value upon what you are exchanging your for - and vice versa for the other party - in order that each might gain what is of greater value to them, and so in the context of that exchange, an objective value is created.

Pay especial attention to what the defenders of 'Economics' mean by rejecting the 'subjective theory of value' - they mean that

your judgment of what is objectively prudent to you, is of no 'objective' (by which they mean an object, a thing, a factoid of empirical data) value, it isn't *real*, and so it needn't be considered or respected in the policies they advocate. That same underlying POV and justification is what's behind their enthusiasm for their curves of 'income distribution' and 'human capital', in that

your judgement is dialectically rendered as being of no concern, as

only material operations matter to them.

Fundamentally they are rejecting the value of

your judgement, to

your life, in

their economy.

'Economic Factors' ranging from minimum wage, to cost of living, interest rates, etc., are used, and revised as needed, to elevate the needs of society as a whole, over the 'anecdotal needs' of any one member of it, and if the smooth running of the 'Greater Good' magic show requires ejecting some members of the audience, well, sorry, but 'Rentier' that you are, that's for the best too.

As you see that for what it is, you'll soon notice that contrary to the ideological pretentions of the Marxist LTV, value is not some material thing that is being

taken from one person, and given to another, through some 'systemic' transferring of materials or money from the oppressed to the oppressor, but is instead, by the very nature of what is actually being engaged in by those engaging in it, value is the benefit that is

created by each party voluntarily exchanging something that is of more value to the other party than it is to them, in exchange for what they've judged will be of greater benefit to them and their interests, so that each

is better off because of that exchange -

that's the growth by which an 'economy' grows! That same growth is what a top-down command economy eliminates the possibility of, and so

ensures the failure of socialist/communist systems.

In a Free Market, Value is ultimately neither a thing nor an effort expended in generating it, but is what results from thought being put into mutually consensual action, and whether that thought in action originates from your own volition, as with the owner of a business that offers a product or service, or as the employee who carries out those thoughts and actions which were initiated by their employer, or as the potential customer's decision to act by purchasing what has been produced, the reality of Value in that exchange, is revealed through their all having agreed in the exchanging of it.

There are very few things in society that are more magical than the plain reality of this.

"

But Van, what if they didn't get what they bargained for?!" That proves, rather than disproves, the nature of Value - if they misjudged the benefit to them of what they exchanged, the overall value of their property will have been diminished by that error, without a single additional item or effort having been engaged in. But if they truly didn't get what they'd agreed to in that exchange - if they were conned or otherwise defrauded - then a crime has been committed, and, assuming the exchange did occur within a Free Market, they'll have some recourse for that through their judicial system.

'

But Van! Don't you realize that government must step in and save us from market distortions, and stagnation, and inefficiencies...' Oh yes,

do tell about the long and glorious history of government interventions that have eliminated market distortions, stagnations, and have generally made our lives more productive and efficient (see the UCLA Economics study of how

FDR's 'recovery' extended the Great Depression by 7yrs)!

xTwitter'rs tell me:

'...Rentiers distort resource allocation by directing resources towards rent extraction rather than productive uses. This can lead to inefficiencies, stagnation, and increased economoc polarization as resources are misallocated and economic rents accrue to a few rather than being reinvested into the economy...."

If you look into such claims of 'economics', you'll find impressively lengthy theories and calculations 'proving' their assertions & dire warnings, which we are supposed to accept as justifying their dismissing what we can see in our own lives is real and true. Just ignore the reality that we agree to pay rent for a property, because we

agree that the landlord is providing a value to us in that property he's maintained, that we are renting from him, just ignore that we invest in a company because when our judgement of their competence is correct, we receive some monetary value from their having brought more value to their customers.

'

But Van! Don't you realize that rent-seeking behavior leads to underconsumption!', which the economically minded assert justifies overriding our puny individual interests and assessments - and the right to make them - in service to the common/greater good. I have some questions, such as according to who, and by what means, were they able to examine not only the needs, judgment, and interests, of the those individuals involved in renting, and those renting to them, but also those of the entire market? And how will they determine 'the best' decision that

should be been made by government for all parties concerned?

xTwitter'rs tell me:

"...Ultimately, rent-seeking behavior leads to underconsumption, where insufficient aggregate demand.

Imo rentiers have to be eliminated through policy so that productive investment, circulation and stability is promoted...."

[emphasis mine - note it]

How do they determine the unforeseen consequences that eliminating rentiers' through policies' will have, upon the rest of those involved in 'the economy'? They only want you to consider that which is seen, and to ignore that which is not seen. They want you to dismiss the reality you can clearly see (metaphysics), they want you to ignore what you understand will follow from that (causality & logic), and to disregard what you understand should be done about that (ethics), and to top it all off, they want you to forget Henry Hazlitt's One Lesson and the importance of considering not only the immediate results of the actions they propose, but what will result in the long run. That concern of Hazlitt's was perhaps most honestly addressed by the economic Wizard John Maynard Keynes, in his "

The Quantity Theory of Money", as:

"In the long run we are all dead"

, and what they want most of all, is for you to dismiss what

IS Good, over any period of time, for the 'Common/Greater Good'... which... truthfully amounts to the same thing.

By what means does anyone attain to such

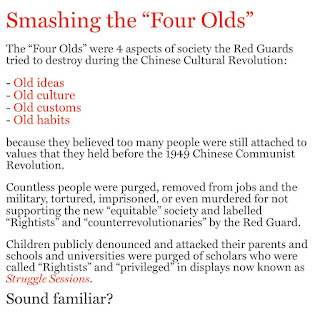

asspoundingly colossal levels of arrogance? Oh yeah... through 'economic thinking'. Never forget that Communism slaughtered 100 million people across the 20th Century for 'The Common/Greater Good', and did so by simply lying - the pen is horrifically mightier than the sword.

Given the nature of such theories, how are we to assess their actual value (and to who)?

What is the value of any theory? Is it the impressive mathematical abilities demonstrated in the calculations and scope of projections that are made by it? Is a theory justified by how well it recognizes & describes reality while identifying and conforming to its limitations, so as to observe, understand, and employ valid principles in making factually verifiable and accurate predictions which follow from that theory?

It's often useful to turn such questions around a bit, and ask ourselves: Why do we abandon a theory? Because it ceases to intrigue us or fails to flatter our current opinions? Or because we come to notice that

reality isn't what is guiding, clarifying, or being revealed, by it?

If you find yourself struggling with that, you should take to heart the example of a decent physicist, who, absent the introduction of a consequential new theory, wouldn't bother with spending another moment of his time on deciphering the elaborate calculations and predictions presented to him in a paper, once he realizes that the plans were for a perpetual motion machine. Once a physicist realizes that those calculations, however impressively elaborate they may be, are made in futile service to what in principle

cannot be supported or achieved, then he'll dismiss it out of hand, just like that, tossing it away as utterly meaningless and worth less than the paper it was unfortunately printed upon.

Once you can avoid focusing on the distracting numbers and dire oppressor/oppressed warnings of doom being waved before you, you begin to see what value LTV has to them, 'economically' speaking. LTV is the wand that the magician's waving before you in grand gestures, which, when combined with his pretty and efficient assistant, and his numerical sleight of hand that makes the rabbit (you) disappear from the hat (economy), you'll see how it enables them to portray Profit, Landlords, Rent, Business Owners, etc., as 'non values', and mere parasitical leaches and thieves -

no Labor, no Value = the oppressors of the oppressed! - in a dialectic that has served for nearly two centuries now, as the fertile entry point for envy and evil to spread out into the various ideologies of popular public opinion.

But there's a side effect from accepting LTV, that's even worse than the theory itself, which was and is an essential component of what Marx most sought to accomplish.

Most people today are familiar with the relativistic claims that any claim to objective truth is nothing but your subjective preference. But the dialectics of

'Your truth isn't my truth', pale in comparison to the wrongs that are successfully smuggled into popular opinion, by claiming that what truly

is a subjective process (all thought originates within a

subject - AKA: you - whether or not, and how consistently a person seeks to objectively conform their thoughts to reality, is another matter), is nothing more than a deterministically 'objective' material process, i.e. 'You don't think, you don't choose, your consciousness is but a side effect of genes & chemistry'. Do you hear Hume & Kant in that?

|

| ...This is what the 'New Economic Thinking' is opposed to. |

What's accomplished there, is that first their philosophical views deny our ability to know reality as it is - deterministic or otherwise - then the materialistic ideas LTV drives forward, effectively eliminate your individual thoughts and concerns from their collective consideration, which becomes the primary means of laundering their most fantastic illusions, into a presentable approximation of reality ("

...Janet Yellen said today that the latest GNP & Jobs Creation numbers indicate to the FED that the economy is continuing to improve..."), which ensures that the only 'real' decisions made, will be those that are made under its auspices, top down, from the T.U.R.D.'s of 'Economics', on downhill to you.

That also ensures that what the Political Economy of Smith, Say, and Bastiat, had exposed as being fallacies, pretenses, and abuses, will be easily ignored by them, and so the confused and chaotic errors which those fallacious actions will continue to flood into the market, diluting, confusing, and worsening all available information, leaving people helpless before the sluggishness of its 'supply chain issues', inflation, and the market's increasing inability to respond to individual interests and needs, in a vicious cycle that can and will only ever make matters worse, while causing people to demand '

action!' to stop the bogeyman from tormenting them - AKA: a totalitarian's wet dream.