'Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion'Claiming that Hume woke him up from his 'dogmatic slumbers', Immanuel Kant decided to oppose Hume by going even further with his systematic assertion that we can't ever really know the reality of the 'thing itself', and deeming earlier 'believable truths' to be outdated and 'uncritical', he led the moderns in systematically revising philosophy's role away from pursuing wisdom, and into providing convoluted sets of high-minded rules and rationalized 'truths' that they'd determined 'would be best' for society to treat as if they were 'realistic' and 'true'. And that system of German Idealism, is what the modernist's new '4th branch of philosophy' sprang from, and is what the word 'epistemology' was coined to obscure behind a facade of 'Greekness'.

For those who'd rather engage with ideas that actually help them to better understand themselves, the world, and how to live a life worth living within it, they'd do best to avoid the presumptions and practices of modern 'epistemology', and instead rediscover how premodern philosophy put what that word claims to mean - a theory of knowledge that distinguishes justified belief from opinion' - into action. The premoderns accomplished that through the only possible means of doing so, by establishing what is real and true, demonstrating how to soundly argue to affirm or refute claims about that, and by identifying what if anything should be done regarding that, which they did through the unified use of Metaphysics, Logic, and Ethics.

|

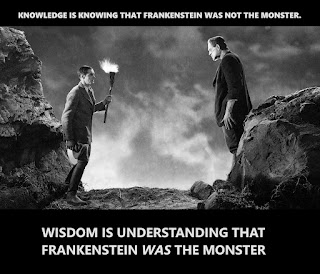

| Knowledge without Wisdom is Monstrous |

In coming posts we'll look at the details of how the modernists did what they've done and the subsequent ill effects that's had on the lives we now lead, but first, to avoid falling into the Inigo Montoya trap which the moderns stumbled upon with 'epistemology' ("You keep using that word... I don't think it means what you think it means"), we need to look at the meaning of the word Ethics, which is generally defined as:

"Ethics: Moral principles that govern a person's behavior and conduct", and perhaps the 1st thing to point out is that Ethics is more than merely rules of 'behavior and conduct', Ethics was traditionally the 3rd branch of philosophy, and contained the subjects of Politics, Law, Economics, and more, which matters a great deal to how philosophy 'distinguishes justified belief from opinion', and despite modern epistemology which concerns itself with that in name only, an ethical concern must be involved in any effort to understand what is real and true and how to respond to that, lest you reduce your own mind to that of an artificial intelligence like ChatGPT.

How do I mean that? Like this: it is not possible to meaningfully pursue the purported meaning of epistemology, without ethics - how would you justify - 'justify' being a term of ethics - belief, while having no belief in, interest in, or concern for, what is right and true? What can 'justified' possibly mean without a regard for what is real and true, and what, if anything, should - 'should' is also an ethical term - you do about that? Should you say anything if you notice an error in how something's been justified? What if that'd be inconvenient for you? Does it matter if you don't? Given its treatment of such stated concerns, it's not so surprising that modern philosophy has spawned a succession of evermore coldly antagonistic and brutal ideologies (utilitarianism, materialism, socialism, communism, pragmatism... etc.,), whose ideals are in constant competition to 'manage society', while agreeing only upon the belief that what is real and true, doesn't matter and can't be known by anyone anyway.

The truth is that it is not possible to be concerned with what we are told 'epistemology' means, without incorporating an Ethics that's more worthy of its name, than the '4th branch of philosophy' is of its name - the desire for knowledge without ethics, is a lust for power unburdened by wisdom. Or, to fit it to the season, knowledge without wisdom is monstrous.

Taking a different tact with the 3rd Branch of Philosophy - differences of degree, not kind

How we approach Ethics, necessarily has to differ from how we approached metaphysics and logic in the previous two posts (here, and here), and you can see why in the differences between the first two of the three philosophical questions, in relation to the third - they are again:

, in that the first two are concerned with what is, while the third is concerned with what should be done because of what we understand those to be. The principles of Metaphysics and Logic rest upon what Aristotle identified as being the first rule of thought, that a thing cannot both be and not be, at the same time and in the same manner and context, and as Logic is entirely derived from that and exists to root out any such contradictions in our thinking, both fields have remained essentially unchanged from Aristotle's day on down to ours, and rightly so, because they are concerned with the timeless First Principles of what is. But as Ethics is concerned with how to respond in respect to what knowledge we have of what is real and true, and as the scope and depth of our knowledge and understanding has expanded and deepened, what is understood to be ethical in relation to that knowledge, has necessarily changed as well.

- 'What is this?', (metaphysics),

- 'How do I know that? (Logic)',

- 'What, if anything, should I do about that? (Ethics)'

Put another way, imagine a scene viewed through a telescopic lens, where you see the ground of a yard with a house upon it and a nearby tree being the tallest figure within the scene - then as you zoom out, while the ground remains at ground level, the single house is seen to be one of many houses in a neighborhood, and the tree which had been the highest point visible has become dwarfed by the mountain which had been obscured behind it when zoomed in. Similarly, while the ground of metaphysics and logic remain solid and unchanged, as their ethical high ground had been raised upon standards that are now understood to be considerably lower from our perspective in time, so that what they saw as the high ground back then, we can now see as standing lower, overshadowed in places, and in some cases is now even seen as being disreputable, if not downright evil.

Because the fundamentals of what we accept as ethical behavior, are nearest to the timeless principles of metaphysics and logic which they are derived from, what we believe to be right and wrong in relation to those fundamentals (virtue, murder, theft, etc.,) change very little over time.

But. Since the breadth and depth of knowledge available to us has grown far beyond what was understood when the philosophical pursuit of wisdom was begun by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, that enables a difference in ethical perspective that's often glaring to our eyes today, which was unavailable in their own time. So that where on the surface there seems to be a common baseline understanding of what is ethical - murder was wrong in their time, as it is in ours - what was thought to be an ethical application of that knowledge can differ as much as its scope - i.e. the understanding of what does and does not constitute murder, has changed a great deal between their day and ours.

For instance, you've heard of the term 'decimated'? That comes from the Roman army's practice of discipling poor performance of the soldiers by lining up the troops and going down the line and killing every tenth soldier where they stood. In their eyes, that was not murder, that was simply maintaining discipline.

That's how much degree can vary within kind. And the more closely you look into the past, the more such differences of degree are revealed.

For instance, on the one hand, there were numerous positive developments over even the course of the 300 years from Socrates' time to Cicero's, where their knowledge and experience of the nature and purpose of the state (government and politics being a subset of Ethics), had further developed the idea of a Republic, into one that contained features of democracy, oligarchy, and monarchy (which was hugely influential on our founder's thinking). Also, the character and performance of the Roman's idea of a Republic depended greatly upon the character of their people, and especially upon the importance of the family unit. That also compelled them to seek out and admit more input from the people, and so they also began to see that The Law needed to be much more than an arena for verbal gamesmanship and rules for the rulers to rule their society through - which was the norm in Socrates' time - and instead needed to be based upon a principled understanding of right and wrong, which needed to be able to stand up to reasonable scrutiny, in order to be considered sound and acceptable as law (see especially Cicero's 'Republic' and 'The Laws').

On the other hand, while these were important and sound advances, advances that could be foreseen only dimly, if at all, from Socrates' position in time, from our perspective perched high atop of their shoulders, we're able to look back and down into their details, and see problems which they could not. For instance, as important as the family was believed to be by Romans to the Roman way of life, the near total power that the Roman Husband/Father, the Paterfamilias, had over the lives of his wife and children - he could put either to death if they had in some way (determined by him) dishonored the family - is something we're able to see today as being intolerably wrong and corrupting. And for all that they'd advanced in an understanding of the Law, and of Government, it was not uncommon for leading citizens and politicians, from Lucius Cornelius Sulla to Marc Antony and Octavian (later Augustus), to issue proscriptions for the good of the state, in which were listed the names of hundreds and even thousands of people who were to be hunted down and put to death, based solely upon the say so of whichever eminent figure had put their names onto that list - Cicero himself met his end in that way.

|

| Death of Cicero |

Those differences in degree, follow from not just ignorance, but from the scope of knowledge and understanding that was available to them. In Aristotle's day at the opening of the philosophical pursuit of wisdom, the good of the polity, the state, marked the upper limit of known value and virtue, and that meant that the value of the individual was measured by their ability to serve the needs of society and the state. It was from that perspective that it was believed in Aristotle's time:

Our very different takes on those situations today come from our present vantage point (or at least one that was common to us in our Founders' time), which sees the purpose of the state to be to

- that the state 'should' direct the education of its youth,

- that some men were naturally slaves and so should serve their masters,

- it was considered perfectly acceptable for unwanted or disabled children to be 'exposed', tossed out on a hillside, where, unless retrieved by a stranger for some desperately specialized slavery, they would die of exposure to the elements or become food for the wild things and vultures.

The vantage point from which we see those situations so differently today, comes from the considerably expanded scope of knowledge and understanding of what a person is, and what a society should be, which was largely unknown and unavailable to them in their time - but we cannot forget that our vantage point is built upon the foundations which they laid.

- uphold and defend the rights and property of the individual within society,

- treating people as property is seen as an evil that is fundamentally opposed to the individual rights which it is the purpose of the state to safeguard,

- leaving infants for dead is seen as murder and an intolerable evil (*cough* abortion *cough*).

Note: Far from this being an argument for 'relativism', it's in fact the very opposite, in that it is because the range and scope of what we know today - not just in quantity, but the height and depth of understanding that is available today - that it's possible for us to see more clearly what is right and true and good and proper in relation to what is and can be known, than could even be imagined in the absence of that understanding. Note Also: Attempting to reverse that perspective, to judge them by the wider perspective of our day which they lacked, is being anachronistic - imposing something from one time, out of place upon another - and should not be engaged in, as doing so doesn't make you look superior to them, but only shows your judgment to be inferior to the knowledge that is available to you.

And yet, the differences are worth noting, if only to highlight the importance of understanding what is available for you to know, and the enormity of what can be missed through ignorance.

It's also important to point out that a vital part of what made our elevated perspective possible - even imaginable - to us today, are due to the major additions to knowledge and understanding that came from the Christian quarter of what was fast becoming the Greco/Roman-Judeo/Christian West, and that raised the bar in ways that truly were inconceivable to Aristotle, and to Cicero as well.

In addition to the four Cardinal Virtues that had been known to them - Prudence, Justice, Courage, Temperance - were added three more virtues of Faith, Hope, Charity, which altered how the original four were understood to be applied. And so, in holding that violence was not only wrong, but that every person was made in the image of God, it was able to be understood that every person - child, mother, father - should be seen as equally human in the eyes of those whose own eyes had been opened to that. From that perspective it gradually became more and more difficult to not see the rich & powerful, as well as their humblest servants, as being equally human, and so equally deserving of the mutual respect and civility that should be extended to all as members of society.

The (very) Slow (then really fast) Progress of History

We today hardly notice how revolutionarily new these innovations were, and many today even cynically treat them as being outdated - not as a result of any new knowledge of ours, but out of a new ignorance of our old knowledge. What we miss, at the very least, is that these new ideas were such that within a remarkably short time they'd defeated the 'gods' of mighty Rome, within Rome! True, they couldn't stop the rot which centuries of corruption had already brought Republican Rome to ruin, and raised the Roman Empire up in its place, but Rome was able to continue on for another two centuries in the western half of the empire, before collapsing from opposing forces within and without at around the 400s. OTOH, the eastern half of the empire in Byzantium - which had never stopped thinking of itself as Rome - endured and prospered for another thousand years, before it too was finally defeated, though more by external forces than internal failures (though those last weren't lacking).

Centuries more passed by before Thomas Aquinas was able to bring that new Christian understanding, into Aristotle's philosophy, while the 'little people' continued to receive very little benefit or recognition of what we would understand today as 'individual rights', and even once violence, slavery, and immorality, had been brought into clearer disrepute, there were still few substantial barriers to stop the powerful from abusing the weak, as 'needed'. As the centuries passed, the ideas began to bubble up as with England's Charter of Liberties, and still centuries after that before monarchs began to be bound to respect the lives & property of their subordinates (barons, earls, etc.,) began to be codified into British law with the Magna Carta, and still several centuries more before people would begin to see that those same rights should be extended to the non-aristocratic population as well, and only then was the understanding expressed by Sir Edward Coke, able to begin to be infused into British Common Law with the idea that 'Every man's home is his castle', and the corollary realization that everyone's 'Castle' depended upon everyone recognizing that every person was due the equal protections of society's laws which were to be defended by the state, against all enemies, foreign & domestic.

With the solid foundation in fundamentals provided by the early Grecco/Roman half of the West, expanded and humanized by the Judeo/Christian half, and refined over the course of the developments of Europe and especially Britain over the course of two thousand years and more, their accumulated experience and discoveries and knowledge, eventually achieved such an elevated understanding as what began to be expressed with the idea of the English 'Bill of Rights'.

The ethical development of the 'Rights of Englishmen', was a tipping point, spanning as it did across Ethic's subsets of governance, law, economics, and societal norms, and became a new norm that America's Founding Fathers refused to relinquish it, even though England was clear across the ocean. They soon set about refining the idea further still, and then extended the theory of its applicability to mankind as a whole, with the understanding that not only did and should the choices of individuals have value and standing before the law, but that government must be barred from infringing upon those fundamental individual rights. With that understanding becoming widespread, a new soundness and prosperity of their entire society soon followed, and hard on the heels of that came the realization that it all depended upon the people having a moral and liberal education, because an uneducated people, as John Adams put it:

'...would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net...', and so it was seen to be necessary that each person's choices and rights & property, would be respected and defended against forcible interference, through the principled Rule of Law, which even the State and its officers were to be held accountable to.

|

| John Adams: '... would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net...' |

|

| What beliefs that are justified without reality, looks like |

Ethical understanding is developed from what we know, and that cannot be ignored in any attempt to identify a 'theory of knowledge for justified belief', and it is our ethical responsibility today to carry that on, which means that you cannot blindly accept the judgments of any time - theirs or ours - without giving reasonable consideration to what is right and wrong, if only to ensure that you understand what you're doing and why, rather than timidly obeying a set of rules that then can have no meaning to you.

Because we have abandoned our ethical responsibility in what we accept as a 'theory of knowledge for justified belief' from modern 'epistemology', we now thoughtlessly accept almost any rule that experts tell us is 'justified', and it has taken less than a century of that for our own people to become largely unable to see what had been seen as self-evident in our Founders' era.

We'll take a look at how the three branches of philosophy work together and are embedded in the ethical virtues that need to be recognized in order to defend against that, and the key epistemological method that was used to blind us to all of that, next.