How we determine what is true with some degree of confidence (which should not be mistaken for infallible certainty - that's not an option for the human mind), is more of a question for epistemology, than for metaphysics. Before attempting that, we first need to be more mindful of how it is that these concepts and first principles of metaphysics help us to integrate our ideas, and add clarity to the process of thinking, and how disintegrated, unnecessarily complicated, and confused, even hostile ('That's "your truth", not mine!'), our thinking becomes when we're neglectful of them.

In previous posts concerning the progressive regress of education in America, I've covered a fair amount of the 'Why' behind why we're no longer taught to be mindful of the basics of metaphysics, and it was with his awareness of the causes behind a similar widespread lack of that clarity in his day, that Aristotle wrote of the need for a science of first principles (in his day, 'science' meant only a methodical study, it'd be nearly two thousand years before the term 'science' would break off from the mother-ship of philosophy and become the quantified method of experimentation that it is today), in Book 1, Chp 1, of his Metaphysics, that:

"...And these things, the most universal, are on the whole the hardest for men to know; for they are farthest from the senses. And the most exact of the sciences are those which deal most with first principles; for those which involve fewer principles are more exact than those which involve additional principles, e.g. arithmetic than geometry. But the science which investigates causes is also instructive, in a higher degree, for the people who instruct us are those who tell the causes of each thing..."Being unfamiliar with the metaphysics which Aristotle noted most people were least likely to have a solid understanding of, leaves us with an illusory cushion between our thinking and the gritty details of reality. But as with the 'chandelier' noted previously, those assumptions too easily lead us to behave as if we 'somehow' grasp enough of the details contained within them, when in fact we know more about our assumptions, than the realities which our inattentiveness is shielding us from. On a related note, despite the caricature of moral and virtuous people being cluelessly 'above it all', because true morality and virtue are rooted in sound metaphysics, those who are truly moral and virtuous are far more aware and connected to reality than the supposedly 'hard edged' skeptic ever will or can be. But that's for a later post as well.

Keeping the Western mind more focused on and in touch with what's real and true, was a lot easier when we consciously kept one foot firmly in each of our culture's Greco/Roman - Judeo/Christian foundations, and the first principles which they were formed from. As noted previously, we aren't ignorant of these concepts because they're difficult to grasp, but because they go untaught, and it's because they go untaught, that we're enabled to remain ignorant of their importance in our lives. Fortunately, the concepts themselves are mostly simple - that's why they work - and we only need to develop the habit of attending to what they otherwise keep out of sight, to benefit from them. For instance, there's nothing complicated about Aristotle's simple test for whether or not a fact is true:

“To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true”True or False, it is what it is, right?

OTOH, their simplicity and similarity to other concepts, is where our attention is required in order to make those distinctions between them that inattentiveness otherwise too easily lets slip past us, and equivocation - false equivalents - can introduce small errors that can grow, or be exploited into, larger ones. One such difference that's worth noting, is between what we can see is 'True', and what is meant by 'Truth' - do you see the distinction? We say something is true, as a judgment about a claim, but what Truth is, is what it itself is, which is different from a judgment about it.

Taking up the thread from Aristotle (and Plato), Thomas Aquinas put what it is we mean by what Truth is, as being when our thoughts correspond to what is real:

“Veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus” (Truth is the equation of thing and intellect), meaning that Truth itself is the general quality of our understanding conforming to what is real; and True is that particular judgment which identifies that a particular thing 'is what it is' - if you hold up an orange and say "This is an Orange", I'll acknowledge that this particular judgement of yours is True. As Aquinas put it, restating from Aristotle, that:

"...the judgment is said to be true when it conforms to the external reality. Moreover, the intellect judges about the thing it has apprehended at the moment when it says that something is or is not. This is the role of "the intellect composing and dividing."..."When you give the matter some consideration, it seems obvious enough, but it turns out that this most commonsensical of concepts, is ground zero in the philosophical and spiritual battle we've been engaged in for nearly all of modernity.

So with just a few basic metaphysical principles: that reality exists, that what exists is intelligible, that Truth is our understanding conforming to what is real, and that discovering and acknowledging what is true is of the utmost importance to a life worth living, we have what were and are recognized as being vital by both halves of our Greco-Roman/Judeo-Christian cultural foundations. I'll save the details for later posts, but the first significant shot felt around the world in modernity, was fired upon those foundations by Descartes, with his claim that since reality could always be doubted, the only thing that couldn't be doubted, was whether or not you were in doubt about something within it (or 'it' itself) - meaning... that... rather than Truth being what you have when your thought conforms to reality (and is therefore able to be verified against reality as being true), the new arbiter of 'truths' became whether or not you clearly and distinctly believed that your own thoughts agreed with your own thoughts, and were therefore 'true'.

Through this new doubtful formulation, people soon began imagining that their own thoughts could subdue reality simply by doubting it, as what you don't doubt about what you think, became the 'truth' - 'my truth' - that the remainder of your thoughts should conform to (and of course if some fudging of 'facts' was needed to maintain that conformity, so long as you didn't doubt that it was needed... it was. (Shhh!)). Descartes' blending of pervasive skepticism with strident certainty in his philosophy and 'Method of Doubt', has intrigued Modernity into a labyrinth that soon after began to enclose and imprison us within it, and in a very real sense, only the earlier understanding of Truth can set us free of it.

Not surprisingly, the weapon that the modernist most often uses against what is real and true, is an inexhaustible supply of artificial and causeless doubt. Since Descartes' day, Kant gave the term 'doubt' a more respectable suit of clothes in the form of 'the critical question' (and which Marx much later weaponized as 'subject everything to relentless criticism'), and any reality the modernist desires to be free from respecting (made easier by Kant's declaring we can never really know reality 'as it is'), they simply and endlessly doubt the truth of it, typically by demanding endless 'proofs' of the self-evident.

But what more can be said about Truth, than that it conforms to reality?

Believe it or not, that question is a bit of a metaphysical minefield which you should approach very carefully, because as ideas have consequences, so does engaging with ideas that don't respect the metaphysical guardrails of reality that are meant to keep you on the road to objective truth. The question that should be asked before going down such paths, is not what more can be said about Truth than that it is what conforms to reality, but what would the attempt look like, and should we attempt to say anything more about it, than that?

What would attempting to do so entail? Wouldn't seeking 'something more' require either using some notion that's even more abstract and so further distanced from what is real and true, or by using something... else ... that'd require referencing something that doesn't exist and so is unreal... to verify what is real? Wouldn't you need to know what is real (i.e. self-evidently true), in order to identify what isn't real, in order to use what isn't real, to verify what is really true? Didn't that thought just take our thoughts and spin them around in a circle?!

There are of course some issues that require us to come at them from other perspectives, but a perspective that requires circular thinking and endless regress, will never be one of them. Such practices that lead into self-evidently circular reasoning, will quickly sweep your mind up along with it, but as a general rule, what is even better than exiting such loops, is not entering into them in the first place. A grasp of metaphysics helps us to avoid such traps by identifying their hazards and keeping our attention upon what is real, while exposing what is not true, and cannot be.

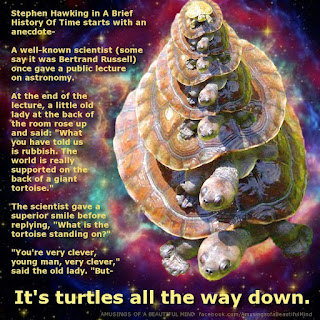

The stubborn fact is that it is unreasonable to ask for an argument to demonstrate what is already self-evident, it is unreasonable to demand a 'proof!' that by definition cannot be logical, because the attempt would fall into an endlessly circular regress of 'explanations', which could add nothing more meaningful to the discussion than the endless assertions of the Turtle Lady. The Turtle Lady being the apocryphal story of an old woman chiding an astronomer for saying that the earth revolves around the sun, when, as she says, 'Everyone knows the earth rests on the back of a turtle!'. The astronomer peers at the old lady over his glasses and says to her "If the world is resting on the back of a turtle, what is the turtle standing on?", and she replies 'A larger turtle, of course!", and before he can ask what that turtle's standing on, the Turtle Lady replies as anyone who seeks the comfort of meaningless circularity, does :

"I know what you're doing sonny, but it's no use, it's turtles all the way down!"Truth is thought conforming to reality, and it's not being thoughtful or deep to seek something 'more' through an endless circularity of ever-receding series of explanations which must mean less than that. It is important to realize that the Turtle ploy isn't about the 'turtles' - it's about getting away with an infinite regress of 'all the way down', which enables them to seem to say that there is something that they mean to say, without ever identifying what it is that they say that they mean. The ploy is deployed by modernists & post-modernists alike to distract you from the nullity of the assertions they're perpetually spinning their wheels in, as a surefire means of getting away with their signature circular spiraling down into nothingness - which is what everyone from Hegel to Heidegger to Kimberle Crenshaw have used and do use to separate minds from what is real and true - and they'd like nothing more than to suck you down into that infinite loop so that you'll become as miserably lost within it as they are - misery, and nihilism, love company.

If you want to get a firm hold upon the truth that modernity has alienated itself from, then brush the likes of the Turtle Lady, Descartes, and the rest of modernity aside, and return to the metaphysics which gave us our first solid grasp on our world in the first place, and which will steer you clear of spinning your wheels in such follies.

The key to keeping your premises conforming to reality, is to begin by adhering to the first principle of thought, which Aristotle identified in the fourth book of his Metaphysics, as the law of non-contradiction:

"...For a principle which every one must have who understands anything that is, is not a hypothesis; and that which every one must know who knows anything, he must already have when he comes to a special study. Evidently then such a principle is the most certain of all; which principle this is, let us proceed to say. It is, that the same attribute cannot at the same time belong and not belong to the same subject and in the same respect; we must presuppose, to guard against dialectical objections, any further qualifications which might be added..."That a thing cannot both be, and not be, in the same manner and context, is inarguable and incontrovertible, and is the fundamental requirement of all knowledge. Even attempting to deny that (which Hegel did, and the Woke still do - we'll get to that in the next post), is to entangle oneself in inconsistencies and contradictions which simply cannot be, and once we acquire the habit of making ourselves aware of the simple concepts involved, no honest person would or should support any such claims.

What we know of reality begins with what we can perceive of it, and however high-flying an ideal might be, if it is a valid one, it can be traced back step by step to a less abstract and more concrete concept, until you finally reach its foundation in what is objectively real and true, and there's no need to pretend that it's possible to go any further down that road than you have, and it would be unwise to attempt it. As Aristotle goes on to say of those who demand proof of the self-evident:

"...Some indeed demand that even this shall be demonstrated, but this they do through want of education, for not to know of what things one should demand demonstration, and of what one should not, argues want of education. For it is impossible that there should be demonstration of absolutely everything (there would be an infinite regress, so that there would still be no demonstration); but if there are things of which one should not demand demonstration, these persons could not say what principle they maintain to be more self-evident than the present one..."As with the abstract lighting concept of a Chandelier, is built upon a lower level abstraction of a lighting fixture, which is built upon a lower level abstraction of a lamp, which is built upon a lower level abstraction of a candle, all of which are intended to output some measure of that concrete reality of light which emanates from them, as it does from the sun, moon, and stars - the abstract concept of a Chandelier allows for thousands upon thousands of variations on that theme, but what do you say to the person who demands more proof that the chandelier in your hand, is a chandelier?, or who demands that you prove that light provides light? They aren't seeking after what is true, they're attempting to cause you to doubt that anything at all can be known to be true.

Note: Investigating deeper into understanding how something comes to be what it is, as a prism demonstrates that white light is made up of a spectrum of colors, adds to our understanding of the nature of light, it doesn't invalidate or give cause for us to doubt our ability to perceive that light is light. Don't permit a misosophical hacker to instill doubts in you with comments such as "Physics proves that nothing is solid, as what you think is solid, is mostly empty space between molecules! It's all an illusion!", when the fact is that what physics actually shows us, is that solidity in the context of our lives, is made possible by how molecules form and interact across the molecular space between them - that 'emptiness' is what solidity is formed from.

That some people do this by either demands or doubts is undeniable - several post-modernists like Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, all authored papers doubting the reality of authors - but why? Shakespeare, with characters like Iago and Edmund in his head, nailed the point well::

Take but degree away, untune that string,, which the philosopher Peter Kreeft put more plainly in that what confusing or doubting the meaning of our words 'accomplishes' in our thinking, in his book 'Socratic Logic', :

And hark what discord follows.

Each thing meets In mere oppugnancy [loud opposition over the merest trifles].

“Definition is crucial to logic. For a definition tells us what a thing is; and if we do not know what a thing is, by the first act of the mind, we cannot know what to predicate of it in the second act of the mind, and thus we have no premises for our reasoning (the third act of the mind).”It's worth taking notice that very few skeptics or relativists would dare doubt the self-evident injury and pain that your punching them in the nose would cause them to truly experience, yet they'll loudly demand that you fill the rest of your thoughts with doubts about every other self-evident reality you might experience.

What such skeptics, relativists, and out & out liars all depend upon, is being able to slip some detail past us within the abstract, to involve us in positions that contradict some aspect of reality, identity, consciousness, which a more careful attention to the metaphysical details can help spare us from, if we pay attention to what it is that they are saying.

What the meaning of the word 'IS' is, in the phrase 'What is Truth?', is what we'll get into in the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment