Preliminary Questions: How important is how you know what you know, to what you know?

Questions of perspective - Understanding our loss of understanding, and the question of getting it back

Metaphysics: Metaphysician: Heal thyself! 1-4

The Real Choice - Metaphysician: Heal thyself! pt1

What the Reality of the Abstract is - 'What is Truth' pt2

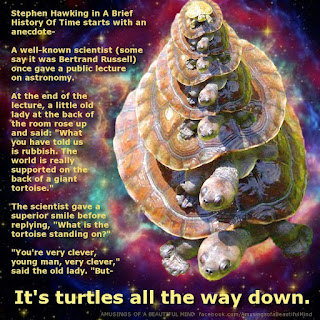

What is Truth: 'it is what it is' or it's 'Turtles: all the way down' - 'What is Truth' pt3

'IS' demonstrates that what is objectively true, is where the action is - 'What is Truth' pt4

Causality & its effects parts a-g

A well rounded knowledge of the root causes - causality & its effects (a)

The Causation of egg on our faces - causality & its effects (b)

Of Cause and Causelessness - causality & its effects (c)

Causation Squared - causality & its effects (d)

Distracting You With What Isn't Actually There - causality & its effects (e)

Facts are only as stubborn as you are - causality & its effects (f)

The Logical consequences of either caring about or ignoring 'What Is Truth?' - causality & its effects (g)

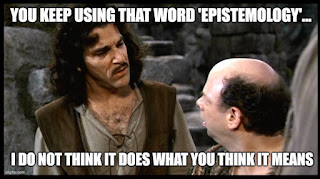

Epistemology: You keep using that word 1-6 (+1)

Epistemology: You keep using that word - 1

Epistemology's meaning is meaningless without Reality - You keep using that word 2

Logic: Observing and deactivating the boobytraps of modernity - You keep using that word 3

The Ethics of Epistemology - Escaping the Inigo Montoya Trap - You keep using that word 4

Would you recognize it if one of your beliefs was wrong? How? - You keep using that word 5

Enlightening the Dark Ages once again: Grammar as an Epistemology worthy of the name - You keep using that word 6

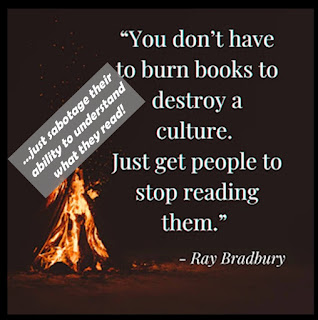

Why are our Culture Wars focused upon winning battles instead of winning the war - where's our Gen. Sherman?!

How important is how you know what you know, to what you know?

Here's an odd question: Do you think that knowledge is relevant to Education? Odder still, how you answer that question puts you on one side or the other of a wide Grand Canyon-like divide in epistemology. Epistemology being:

"...the study or a theory of the nature and grounds of knowledge especially with reference to its limits and validity."And if you hadn't noticed that there was a divide, allow me to point out that if you think that 'Knowledge' indicates something that can be objectively known to be real and true, that puts you on the traditional side of that divide, and then way, way, over on the other side of that divide - where your schools are - are claims such as this:

"...Given that the transmission of knowledge is an integral activity in schools, critical scholars in the field of education have been especially concerned with how knowledge is produced. These scholars argue that a key element of social injustice involves the claim that particular knowledge is objective and universal. An approach based on critical theory calls into question the idea that “objectivity” is desirable, or even possible..." Sensoy, Ozlem, and Robin DiAngelo. Is Everyone Really Equal?: An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education, first edition. Teacher’s College Press: New York, 2012, p. 5, then 7SoOooo... the Woke believe that 'Knowledge' matters, that it matters how it's 'produced', and that it is unjust to teach that knowledge has an objective meaning (a meaning that is objectively true for you, true for me, and true for anyone else, no matter their feelings or prejudices) to your kids, in our schools.

|

| The Epistemological Drama |

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness", and here's a very different claim that depends upon a very different epistemology than that of our Founders:

"We support Diversity, Equity and Inclusion"These two examples represent two entirely different epistemologies, and they are entirely incompatible with each other - each is a refutation of the other - don't you think that you should understand whether either of those statements are true, or false, and how to justify one or the other?

If you know nothing about epistemology - yours or theirs - how are you going to argue the point?

Note: The question is not 'should you use an epistemology?', but rather 'Are you aware of the epistemology that you are using?!' You are using a form of epistemology in evaluating what is 'claimed to be known', and in justifying what you think is worth knowing, but if you aren't at least somewhat familiar with the uses and misuses of how such matters are justified and verified, then your thinking will be muddled, and the other side will roll over your 'b...b...buh..but!'s like a tank.

What does it mean to say that something is justifiable? Ironically, even asking the question means assuming the existence of the same objective truth that the Woke despise, but handily enough for them, denying it also 'frees' them from any such logical concerns, yet it doesn't do away with the fact that the traditional view is not only what our nation was founded upon, but is the True North which our ideas of Education were once rooted in and oriented around. And neither position frees you from the responsibility of consciously considering whether or not "... that particular knowledge is objective and universal...", and whether or not understanding that it's true "... is desirable, or even possible..." - and evaluating how to understand and affirm or deny those questions, is what epistemology does.

The fact is that epistemology sets the tone for every claim - sensible or nonsensical - in our culture, politics, law, and the education of those who go into each of those fields. Sound epistemology is critical to being able to identify and orient towards True North, and unsound epistemology is what we all use to justify wandering off of the straight & narrow, whether that be the sloppiness of slightly astray, or the deliberate thumb in the eye of a 180* turn in the opposite direction.

Speaking of which, as we like to look back on the 1940s and 1950s as being fairly solidly patriotic decades in America, have you ever wondered how it was possible that John Dewey's people were able to send an official invitation to the members of the Marxist Frankfurt School, to come to America and set up shop at Columbia University (more on that invitation in coming posts)? Do you suppose that their cool German accents charmed everyone and got them a free pass? Or... was it that those at the heart of our school systems who were exceedingly familiar with the meanings and justifications of epistemology, even then, understood and welcomed such a radically incompatible set of Marxists into America, knowing that their intention was to undermine and subvert the ideals that America was derived from, and confident that they could get away with doing so?

And yet most Americans, and certainly most students, were unable to recognize what those beliefs meant to their own lives, and to the lives of their children, and grandchildren, and because they didn't recognize the threat, and wouldn't have been able to defend their beliefs against them if they had, we are in the position we are in today where it's not only Academic America that is rabidly and openly anti-American in their beliefs and actions.

If we don't learn to recognize and defend the ideas of those truths that we hold to be self-evident, from the supporters of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion who mean to eradicate them, what effect do you suppose that will have upon your children, and grandchildren, and nation tomorrow?

The fact is that the values and rules of behavior that a society develops, are based upon what they're able to agree upon as being right and wrong, and for that to be possible, they first need to be able to say that something is (which is Metaphysics), and from there we must give consideration to how we know what does and does not qualify as knowledge of it and how to verify it (Epistemology), because only then can anyone have anything meaningful to say about what is right & wrong to do in light of what is known to be true (which is Ethics).

When arguing with someone (which does not mean either fighting or debating) who disagrees with you, you're engaging in a process of reasoning with them by identifying what each of you see from your varying perspectives, and then comparing your initial mental sketches to what you both can see of the actual landscape, and that often involves (and requires) congenially directing and shifting your vantage points this way & that to see things from the other person's point of view so as to compare and find what landmarks you can agree upon - or the lack of them -between your wordscapes and the actual landscape that you both inhabit. Progress in an honest argument isn't marked by a win or a loss, but by finding that your sketches have revealed something clearer - whether that be a mere glimpse or full scenic view - of what can be agreed upon between you, and better understood about each other, and verified, as being real and true, and that is employing and practicing the epistemological process that was implicit in the traditional reasoning that our Founder's era was familiar with.

Under that traditional view, notions typical of its adversary in Social Epistemology, such as 'what's true for you, may not be true for me', would be dismissed out of hand as being unserious and potentially dangerous sentiments that undermines and outright attacks our ability to reason together towards some mutual understanding. It's not looking for an honest (meaning what?) argument, even as it demands the results of one with your agreement (or compliance) without its cause: having reasoned towards a mutual understanding of what is real and true. What they want to avoid at all costs, is an honest argument. Statements such as that are not a call for truce, but a passive/aggressive attempt to verbally overpower your moral objections to their position, which gives them a foothold in your own mind, from your having implicitly legitimized their falsehoods by accepting them as possibly *true* (meaning what?), when in fact what is real and true, are obstacles to the wordscapes they expect you to either accept, tolerate, or submit to. When you nod along with such statements, you're missing the fact that whatever you had thought was important to adhere to, has been reduced to their level as a now meaningless *truth*, as you've surrendered the epistemological battle you didn't even realize you were fighting.

Solzhenitsyn's call to 'Live not by lies' is truly meaningless, if you cannot recognize or defend what is and is not true.

Prior to modernity, the process which epistemology now refers to wasn't seen as being so distinct, intricate, or confusing enough, to warrant being designated as a distinct field of study, as other than a handful of outright cynics and skeptics which most reasonable people generally dismissed out of hand, the fundamentals of philosophy - metaphysics, logic, ethics - already covered what could be known and how we could know it, as naturally followed from Aristotle's first rule of thought, from his metaphysics, essentially that:

a thing cannot both be, and not be, at the same time and in the same context., the ability to give reasonable consideration, and the ability to apply the logical method, follows from understanding that, and through that understanding, a person can be expected to reliably come to know the nature of what they do and do not know, and to understand how they know it, which forms an informal epistemology of how 'you know what you know', and the ability to logically verify it. As a result of attempting to deny that first rule of thought, we now have not only a field called 'Epistemology', and something called 'epistemic adequacy' (that you know that 'it is what it is'), but wildly divergent systems of epistemology which accept and justify 'concepts' that are in conflict with that first rule of thought, and any thought which follows from it. That is of course still the basis of a valid epistemology, and any claim that denies, or attempts to spin that statement, is invalid and an unjustifiable epistemology, as are those ideals and ideologies that are built upon them. And yes, if you know that, and know that their claims are based upon invalid epistemologies, all you need to do is expose that, and their game of ideological Jenga comes tumbling down.

A good first step in that direction: 'What do you mean by 'True'?

We tend to marvel at people not being reasonable today, but anyone who fails to engage in reasoning without anchoring their effort in the reality below their thinking, and with truth as the star above that guides it, cannot reasonably be expected to maintain even the appearances of being reasonable for long. Without a regard for what is real and true, the need to find mutual understanding and a connection to what is true, all 'arguments' and statements must devolve into either conveniences of mutual admiration, or confrontations which can only be 'resolved' through some contest of power, whether that be by tallying up the quantities of 'likes' and 'dislikes' for it, or by physical force or the threat of it, and as Thrasymachus put such notions of 'Might makes Right' to Socrates:

'...I proclaim that justice is nothing else than the interest of the stronger'.Reason without truth is ideology, its aim is power, and its means are the politics of force, which require that the laws of right reason be transformed into arbitrary rules to be obeyed without question, or else. We'll begin taking a deeper dive into what this is, and isn't, and how your ability to know can be undermined, in the next post.

Back to Top

Wednesday, February 01, 2023

Questions of perspective - Understanding our loss of understanding, and the question of getting it back

How sure are you that what you know, is actually so? How sure are you that what your child is learning, is worth knowing? Do these questions seem worth answering? Or asking? If not, does this one give you any concern:

Of course, I think you'd have to follow that up with this:

- What if what you think you know, that isn't so, is harmful to you?

"Is there some situation where believing falsehoods and lies, is not harmful?"Sure, that may lack nuance, but is determining whether you or your kids are going to be eating food, or poison, the place for nuance? Because IHMO, that's the perspective that educational content should always be viewed from.

I've surely made it clear that I've very little (and by 'little', I mean less than zero) respect for the textbooks, materials, and purposes, employed in our schools today, but as bad as the sketchy facts, ideological spin, and lies by omission or commission (hello 1619 Project) of most educational content is, those alone don't have the power to implant their 'key facts' into a bored student's memory, or to significantly alter how they think. How such materials leave their mark on a student's mind has less to do with what's laid out on the page in black & white, than with what questions are asked, and how they're expected to answer them. Schools devote a significant amount of time to drilling in the habit of how students are expected to ask and answer questions (quizzes, worksheets, tests, homework), because that pattern is what will persist in their thoughts & actions long after the 'key facts' and details of their more recent test scores, or total cumulative GPA, have been forgotten.

Sometimes of course, the purpose of a bad question is obvious.

It's easy to spot the 'Have you stopped beating your wife?' types of questions, which can only be there to subvert its subject and demean the student's impression of it, such as with this far too typical question on an exam that was recently given to a friend's child in a local high school:

"17. What were the American motives to imperialize? What are some examples of American imperialism?", and the intentions of such questions are so obvious that, at least in early stages, they quickly attract the necessary outrage of the moment required to deal with it.

Less obvious, and IMHO more damaging, are the more mundane questions and answers which tend to either go unnoticed, or worse, are applauded by parents and politicians alike for being the 'right answers' that flatters the Red/Blue leanings of their own communities (physical or political), with very little thought given to how such 'Ok' lessons might affect the thinking of the students being educated through them. With that in mind, I've got a three-part question that might help alter your perspective when reviewing the various "Things to consider", and chapter quizzes in textbooks and worksheets, and the additional quizzes and tests which are used in sculpting your child's thoughts, and that's this:

Whether that question's perspective is one you're willing to try out, or is one you'd rather ignore, or if you're simply puzzled by it, likely has much to do with how your own education implicitly taught what this question is concerned with, by example, day in, and day out, year in and year out. What it's concerned with is what most 'educational content' typically avoids, which is the stuff of metaphysics (which is not what you find in the 'New Age' section of your bookstore) and epistemology (which increasingly should only be found in the 'New Age' section of your bookstore). Why? Because they govern what we tend to pay attention to, and how we do so, which sets the stage for our deciding whether or not to take one action, or another, or none at all, and there are few things more important, and more commonly ignored today, than that.

- How do you know if a question is worth asking, and whether or not the answer to it is worth being pursued, and whether or not finding it might do more harm than good?

Of course, answering that question requires asking a few more questions, about the types of questions and answers that are being used in our schools, in order to develop how their student's will think about their subjects:

Does the expected answer provide a meaningful complement to the question, and clarify the importance of having asked it? Or are most answers simply 'key facts' to be recalled as 'the answer' whenever prompted ('Remember class, this will be on the upcoming test.')? Some facts do of course need to be committed to memory, and students should be able to retrieve them almost without thinking - math times tables, names & dates of history, the rules of grammar - those need to be effortlessly at hand as brick & mortar for the constructing of sound thinking with. But with other kinds of questions, questions such as 'what caused the American Revolution?', those are matters of a very different nature, and they require a depth of consideration and deliberation in order to reach a depth of understanding which the recalling of lists of 'key facts', and names & dates, and tax rates, couldn't possibly equal.

- Why are the questions there, what's their purpose?

- How are students' expected to answer them?

- Do they help in developing a wider and deeper understanding of what is justifiably worth knowing?

- Are their answers meant to be understood, or are they simply 'key facts' to be recalled as 'the answer', whenever prompted?

For example, the questions and answers that concern me most, are those seemingly innocuous fact-check types of questions, which require more than a simple fact to be answered well, the kind that a quick glance through your school's materials will prove to make up the bulk of their student's chapter quizzes, fill in the blank worksheets, and bubble tests, such as:

- "Question: #1: How is America similar in kind to other nations such as France, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, England, etc.?"

- "Answer: A - each are members of Western Civilization" , or

- "Answer: B - These Western nations are the source of systemic racism and oppression of persons of color"

You see, the more important point has little to do with whether 'A' or 'B' is the expected answer, the point is that whichever one of those answers will get their students a good grade, will 'work' just fine for one community, and vice-versa for the other, and what students learn from that is that what is real and true is not the point of their lessons. And that lesson - repeating the 'answer' that will work, as the answer - is the real lesson that our students are being inundated with, in nearly all of their lessons, worksheets, quizzes, and tests, which is the point that's being missed in nearly every Red/Blue community in America today.

That memorization, and deliberation have different purposes, isn't a new point, only a forgotten one (at best), one that Aristotle was pointing out 2,500 years ago in his Nichomachean Ethics:

"...in the case of exact and self-contained sciences there is no deliberation, e.g. about the letters of the alphabet (for we have no doubt how they should be written); but the things that are brought about by our own efforts, but not always in the same way, are the things about which we deliberate... Deliberation is concerned with things that happen in a certain way for the most part, but in which the event is obscure, and with things in which it is indeterminate..."Of course it's useful for students to memorize the alphabet and 2x2=4, and deliberating over such facts and unvarying results would be a waste of time - memorize them and have them at hand forever without giving them another thought (though some may recall Common Core Math demanding extensive deliberation over just such facts). But what of matters such as the causes of revolutions? Are those mindlessly repeatable facts like 2x2=4? Do such matters always turn out in the same way, or do variations in time and circumstance, tend to produce unpredictable results, such as the differing outcomes of the American and French Revolutions?

What do you suppose happens when a student memorizes a list of 'The six causes of the American Revolution', and is given an 'A+!' for doing so? That's right, worse than such answers being simply wrong or inadequate, awarding 'A's for such answers, gives students the impression that mindlessly recalling lists of facts, is equivalent to understanding the issue at hand, and each time that students are led to ingest such 'answers' as understanding, reduces the likelihood that they'll engage in that type of deliberation in the future, which is what a deeper understanding of such matters requires.

That's what I mean by 'Questions and Answers' that aren't worth being pursued, because finding them might do more harm than good, certainly more harm, than 'getting straight A's!' could ever compensate for. Helping a student to understand what is important, and training students to parrot a 'key fact' on cue, are two very different educational goals, and we need to recognize that when students are being taught and graded in this way, then the primary purpose for the materials, the questions, and the expected answers to them, is to further a narrative and habituate students to getting answers from 'those who know best', and that is the 'educational norm' everywhere today.

Coincidentally (not !) that same approach is what we see being followed daily in our news media, Left and Right, and no doubt the familiar approach is what their successful ratings depends upon: A source declares that issue X is important, 'key facts' are provided, and experts advise that the acceptable answer is A (or B). That familiar approach is what propaganda depends upon and is spread through, and the metaphysical & epistemological methods that are implicit in it, convey its 'answers' that we are expected to accept, and repeat, on demand, despite what can be seen to be real and true by those who bother to look past the surface (See the Munk Debate on the topic of 'Don't trust mainstream media' between Douglass Murray, Matt Taibi vs New York Times celebrity authors Malcolm Gladwell and Michelle Goldberg, and see the latter two cluelessly attempting to use their 'expert status' to define their opposition, and lose badly as scored by the audience, who weren't buying it at all).

Questions worth considering

The funny thing is, that when the point of a question is understanding, rather than boosting test scores, then following in the wake of a reasonably in-depth study of those nations' histories and cultures, that very same opening question can be used between a teacher and their students, as a first step down paths of understanding that are well worth travelling, guiding them into considering something that their lives will be richer from knowing.

- "Yes, America is, like those, a Western nation, but it also differs from other Western nations by degree - often significantly so - how important are those differences to what America was founded to be?"

"Yes, those are significant differences. How is it that, with differences such as those, that the West somehow shares a common literature in works from Homer to The Bible, from Plato to Virgil, from the anonymous poet of Beowulf, to Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Rostand, despite each coming from as many and more different languages and 'cultures'?"When questions have a purpose, they are able to lead to replies that can lead to further questions, and develop into a pursuit of the subject that serves to develop a student's ability to make meaningful distinctions, and even reveal within them a sense of wonder over how such a ... er... 'diversity'... of sources, managed to become woven into the recognizably Western understanding of what is right and true, which both serves and reflects the ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, and yes, religion, which underlies and supports it. It's that broad understanding which has (or at least had) instilled Westerners with a widespread regard for the Rule of Law and a disdain for the arbitrary ultimatums of tyrants who'd demand that their subjects submit or die, which is what the subject of my 'perspective question' is very much concerned with.

So the initial answer to the first part of my question, is does a question lead you into an understanding of what is real and true? If it doesn't, or if it expects you to accept something in place of that, it's because those asking it don't want you to understand it. Is a question being asked in pursuit of what is real and true? If you're not able to tell, or if it settles for a diversion or a simulacrum of that, it is not only not worth pursuing, but it is leading you, either by intention or incompetence, away from what is real and true, and habituating you to continue doing that, which is exceedingly harmful to your education, and to your life.

OTOH, when a student is becoming aware of how and why the questions they are being asked, and the answers they are finding themselves giving to them, not only fit together, but instill in them the sense that something is developing in their mind and body that thrives from their being fitted together, then those questions and answers are leading them to a wider and deeper understanding of the issue, which is a sign that an education is occurring within them. But that sense of understanding will not develop from retrieving approved 'answers' that are taken from someone else's conclusions, for them to repeat as needed for test scores, or for eliciting the politically correct approval of others.

Here then is a question that's worth asking:

Q: Can any form of education which lacks, or attacks, that central Western root, be of use for anything other than the destruction of the West?And here's the only answer that's worth giving:

A: No.Understanding, or data collection and narrative building?

The problem is that while follow-up questions that help develop understanding can come from a teacher orally testing a student's knowledge, that engagement is unlikely, if not impossible, to come from the sort of printed tests with answer keys that we began using in America, as noted in previous posts, after Horace Mann injected them into standard practice for American schools in the early 1800s. As was also noted previously, what Mann especially liked about written tests was, they fostered a data collection strategy which he infamously used as a means for controlling and developing a narrative in public opinion about education, and to control which educators would be permitted to continue educating students in their society, in order to form and control that public's opinion.

Along with the innovation of written tests, came the replacement of original sources with textbooks, quizzes, graded work, and standardized tests, not to mention separating students into age related 'grades', and moving students as the bell rings, from one classroom to another, to study materials that are treated as very 'separate' subjects. The shallow pursuits that have accompanied those innovations, are mostly pointless and trivial wastes of time, which are educationally destructive, and whether that destruction comes by way of a sledgehammer of failure, or the slow rot of getting 'straight A's!', the aims being achieved are the same.

Here's a 'key fact' that's worth recalling: uniform written tests and 'Final Exams' as we know them today, did not exist in our Founding Fathers' era - instead they used oral examinations, where the teacher would ask questions of individual students, who would respond, and be questioned further based upon their responses. None of those features that we now take as normal today, were involved in the education of our Founding Fathers' generation - they had no grades, no test scores, no GPAs - does anyone seriously imagine that they were less educated than our 'straight A!' students are today (see Walsh's 'Education of the Founding Fathers of the Republic')?

I'm not attempting to push some gibberish of 'Grading student's work is too stressful, just let them groove to the lessons!', I'm saying that the system of grading your student's work, is being used to con you - it's not the student's education that's being graded, but your willingness to accept that those grades indicate that your child is being educated!

That realization is what startled Pete Hegseth into realizing that we are all to some extent today, products of a 'Progressive Education', in that we can hardly conceive of the subject without them, and all of those 'experimental' innovations reflect the underlying pro-regressive approach to, or evasion of, what is real and true. And because more and more people are coming to that realization, an education that's actually educational not only can still be found today, they're becoming increasingly easy to find, but it does require looking outside the realm of textbooks and answer keys, where students can be led into observing and understanding just how significant it is that from its earliest foundations in so many diverse languages and cultures, whether coming from our Greco-Roman or Judeo-Christian roots, through the likes of Socrates or Proverbs, the embrace of reality and reason, and a reverence for truth, virtue, and wisdom is what, has been both the needle and the pattern from which the Western ideal has been woven.

The sad truth is that 'education', as traditionally understood, has become a foreign concept to both 'conservative' and 'woke' schools, each of whose texts are primarily used for fact fishing exercises that do little more than train students in efficiently retrieving and repeating approved answers, in order to build up what their [school, school system, community, business, govt, ...?] sees as being a useful narrative, while also outputting a steady stream of useful human resources.

In short: Ideas have consequences, and ignoring how ideas are understood and validated has severe consequences for those who are under the power of those same ideas. That being the case, the question that parents and politicians should be asking, is whether such questions and answers that fill their textbooks and tests are even worth being asked or answered, by any student, in any school at all? Or more pointedly:

What using expensive textbooks, curriculums, and standardized tests, to install 'key facts' into an entire class of students, rather than developing individual student's understanding of what is real and true, is the visible track marks of a metaphysics and epistemology that purposefully does not lead students into paths of thoughtfulness (and couldn't even if it tried). What our students gain with their diplomas, is the false sense of knowing something that they do not in fact have knowledge and understanding of, and that misplaced sense of 'knowing the answers', is what our schools are teaching our students to 'learn', and the habit of fetching & accepting someone else's answers to questions that they haven't explored or understood themselves, is the means by which that lesson is being taught in nearly all of our schools, by example after example, day in, and day out, month after month, year after year.

- Q: Can the purpose of such questions and answers, be educational?

- A:No, IMHO, they cannot.

How you question your answers, matters

The traditional Western approach that began with Socrates, and which Plato and Aristotle and Aquinas perfected, involved a methodical approach to questioning and understanding and verifying that what you know, conforms to what is real and true, a sense that's now called 'Epistemic Adequacy', essentially meaning how to know that "'it,' is what it is", which is the beating heart of the West.

Our founding documents, such as the Declaration of Independence which Thomas Jefferson intended to be "... an expression of the American mind..." were drawn from "... the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c...", which were deeply concerned with, and rooted in, what was understood to be true, and with how you, their reader, could know it. For 'We The People' to be capable of enjoying Liberty and Justice for all under a Rule of Law, we must care about what is real and true, and we must understand how we know if something is objectively true, and to care about how that integrates with the rest of what we're able to know is real and true.

In contrast to the Western standard of 'epistemic adequacy', the pro-regressive 'Progressive' and the 'Woke' are less concerned with what is real and true, than with what their group desires others to accept as 'true', a view that naturally gravitates towards using power to transform 'their truth' from wishes into demands, which others will be forced to accept, in line with the age-old standard of 'Might makes Right'. Those who dare to point out that 'their truth' is demonstrably untrue, will be hit with the accusation of 'epistemic oppression!', because your expectation that their words should conform to what is real and true, interferes with their desire to impose 'their truth' upon you, and they'll berate you at the top of their lungs, for interfering with their desire to abuse you as they please.

For all of their load mouthed bravado, what the bullies and tyrants of Wokeness detest and fear the most, is the Western method of asking questions that expect to find a correspondence between what is real and what is true. That fear is as real to them today as it was 2,500 years ago when their forefathers put Socrates to death for refusing to stop practicing and teaching his method; the same method that Pontius Pilot hurriedly washed his hands of.

The West in general would not, and could not, have grown, prospered, and persisted without an understanding of the importance of asking good questions and then pursuing the answers that follow from them, and America in particular, cannot long endure if our educational system is permitted to systemically muddy or even sever our ability to identify and acknowledge what is objectively true.

The issue with our schools isn't that they need to improve their student's grades & test scores, or that we have to somehow get schools 'back to basics'; the issue is that we need to break free of the narrative of lies that we've enmeshed ourselves in, through the lessons they've been teaching us. If being an American doesn't imply a familiarity with and understanding of the ideas of those 'public books of right' that Jefferson spoke of, then being an American can mean little more in the minds of those living in America, than a checkmark on a legal form, or a geo tag reference on their phone, and if that becomes the case, then neither Liberty nor Justice for any, can long endure within the geographic area legally known as the United States.

Ironically, the modern field of Epistemology was itself first formally created (its methods were implied or contained within classical metaphysics, but it wasn't made into a field of its own, until the assault of modernity began) by the German idealists (Kant, Fichte, Hegel) for the express purpose of breaking us away from the Western habit of rooting our understanding in what you know to be real and true, demanding that you dispense with what can be known (Metaphysics), and dialectically refocusing instead on how we know 'it' (Epistemology) - you might hear the echo of Progressive Education's mantra "Don't teach what to think, teach how to think!".

The clownish complexity of their Rube-Goldberg contraptions of convoluted and equivocal language that these idealists have crafted for their assault, evokes the showiness of the stage magician waving his left hand to distract the audience from what the right hand is doing, and, and what that wacademic abracadabra has culminated in, is the lethal epistemological variant of 'Social Epistemology', as described in the Routledge Handbook of Social Epistemology:

"...Breaking with an ancient philosophical tradition, social epistemology adopts a social perspective upon knowledge, construing it as a phenomenon of the public sphere rather than as an individual, or even private or “mental”, possession. Knowledge is generated by, and attributed to, not only individuals but also collective entities such as groups, businesses, public institutions and entire societies...."That perfectly describes the active process of severing the minds of the unsuspecting, from the traditional understanding that wisdom depends upon their knowing, and knowing what is true, and it is key to what has delivered us up to Cancel Culture of today. For us to recognize and effectively combat that, we, you, need to have at least a grasp of how it has progressed through the questions we ask - or ignore - into our everyday assumptions and considerations, and what I'll be going into in the next few posts, will, I think, give you the basis for doing that, or at least a functional starting point for it. Those who don't bother with even trying to understand how that process works, are - whether willfully or negligently - leaving themselves and their children at the mercy of those who are eager to use their ignorance as a means of gaining more power over them both.

If your own education neglected to inform you of such matters, you have my sympathy - mine didn't either, and it's been a struggle to learn about it on my own. If doing so yourself doesn't appeal to you, again, you have my sympathy, but - and I hope this doesn't come as a surprise - our feelings about that don't matter. If you don't put in the effort to at least familiarize yourself with these matters that are threatening to destroy your children's future and our nation, then both will be consumed by it.

Sorry, way it is. Your choice. And your choice will have consequences.

Back to Top

Friday, April 07, 2023

The Real Choice - Metaphysician: Heal thyself!

'All men by nature desire to know'

Aristotle's Metaphysics, Book 1, line 1

So what sorts of grand and powerful terms are we talking about here? Well... I think 'grand and powerful terms' are part of the problem, as to anyone but academics, the terminology itself (ontology, nihilism, correspondence theory, empirical, existential, causal... ) stands squarely in the way of people being able to grasp and use what it is that they refer to, even as what it is that they refer to - how we all 'do' metaphysics from moment to moment and day in and day out - is routinely handled by each and every one of us through very simple, familiar, commonplace terms. As I list a few of these, keep the adage in mind that 'big things come in small packages' and try not to laugh, because Metaphysics' study of First Principles involves giving respectful attention to concepts that seem to be anything but impressive, a few of which, in no particular order, are:

'is', 'isn't','Truth', 'true', 'false', 'why', 'cause', 'effect', 'identity', 'confirm', 'change', 'experience', 'good', 'bad', 'because', 'therefore', 'sensible',..., and other such equally lofty and dazzling nuggets as those.

My warnings aside, you might be tempted to smile at these seemingly simple terms, but their simplicity can be deceiving (innocently or intentionally), as respecting these concepts are the very things which make a good life attainable and our specialized fields & sciences possible, and they are key to whether our minds can be depended upon to operate intelligibly and smoothly, or instead are prone to become easily confused and abused.

|

| Scientism is unscientific |

"You should only believe a truth that is scientifically verifiable", and perhaps the first thing to notice is that this statement is itself a verifiably unscientific and self-refuting statement - how would you formulate an experiment to scientifically test that with, and with what weight, measure, or Bunson burner, would you quantify its results? Still more worthy of notice, is that neither Truth, nor Verifiable, nor Should, are concepts of science. 'Truth' is a metaphysical concept, 'Verifiable' comes from epistemology, and 'Should' comes from Ethics, and their function is to tell you what is, how you know it, and what to do about it, which when taken together describes how to verify 'the science!', meaning that it's science that is subordinate to metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics, not the other way around! And as ludicrous as the notion is of scientifically verifying all of your beliefs (how is your belief in the value of art to be justified scientifically, by weighing it on a bathroom scale perhaps?), do we even need to note what 'believe' applies to?

The upshot of this is that by attempting to take their statements seriously, their own words are telling you to not believe or take their own words seriously. The problem with laughing such carelessness off though, is that it probably indicates how unaware they are of how far their own beliefs have led them out of the realm of Science, and into the ideology of Scientism, whose "excessive belief in the power of scientific knowledge and techniques" bestows upon its believers the heady power to define Truth itself (not to mention 'right' and 'wrong'). It is especially important to realize that these people who claim the authority to speak for 'science', are, knowingly or not, in hot pursuit of the power to impose their opinion of what the 'smart thing to do' is, upon you, who, after all, lack their credentials for making those decisions about your own life. Case in point, if past performance is any indicator of future results, you'd do well to do some homework on Eugenics, as that is just one example of the horrific mistakes of history which they will be repeating in your future, if our continued carelessness and ignorance of these concepts permits them to do so.

The takeaway here is that when you hear otherwise intelligent people like David Hume, C.S. Peirce, Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson, making such metaphysically nonsensical statements as that above, you should understand right away that not only do they not know what they are talking about, but that they have probably never given any serious thought to the meaning and potentially dangerous consequences of their own thoughts, or, if they have, they don't think it matters, as with this leading advocate of scientism, ticking off 'reasons' for his belief:

"...What is the difference between right and wrong, good and bad? There is no moral difference between them., or, the same sentiment is re-worded in such a way as to shift around the location of the error, to make a distinction without a difference, as Tyson frequently states:

Why should I be moral? Because it makes you feel better than being immoral..."

"The good thing about Science is that it’s true, whether or not you believe in it.", and the problem with this is that it is not proper to say either that 'Science' is true or that 'Science' is the kind of thing one should 'believe' in - neither is true! What Science is, is a method for formulating and determining the accuracy of propositions whose results are measurable, and as every scientist should be well aware of, history has frequently demonstrated that as our ability to measure those results improves, and as changing contexts cause scientists to rephrase those propositions more appropriately, we often find that the results of 'the science' does not in fact continue to warrant belief in the original proposition. That's not a problem with science - that's its strength - that's a problem with those who're carelessly misusing the powerful concepts which 'Science', 'is', and 'belief', are! Even more problematic is that the smugly dismissive statements of representatives such as Tyson, smuggle equivocations and errors into popular thinking, which can all too easily lead those who have even less familiarity with these concepts than they do, into unwittingly believing what should not be believed (hello again eugenics), and that road cannot lead to a good destination (we should give dishonorable mention here to Al Gore and Dr. Fauci).

Physicist Sabine Hossenfelder on the group think of scientists' Lost in Math

The good news is that the circular reasoning of Scientism is self-refuting; the bad news is that the views that such people have popularized in our society, have left a great many people blind to their falsity, and such metaphysical blindness has real world consequences. Giving more careful attention to the metaphysical & epistemological concepts which are so used & abused around us today, would reveal a number of misleading, impractical, and downright dishonest efforts being advocated for, which puts us all at the mercy of ideologs who've become used to the convenience of our enabling them to slip their half-baked notions right past us, and too often with our approval and support.

Metaphysician: Heal thyself!

Metaphysics matters because it helps us to take notice of those big things that so often hide, or are hidden, in small conceptual packages, which, once they've been slipped past us, have an outsized impact on our ability to live lives worth living. Recovering those abilities doesn't require us to learn technical terms or famous disputes over them, it simply requires that we do metaphysics, and to that end I'm proposing a mini metaphysical 'back to basics' exercise over the next few posts to see how the fundamentals are being used around us, against us, and by us, by focusing upon the use of three simple words, which, not to go all Pontius Pilot on you, are:

"What is Truth?"These three words, separately and together, are in one way or another essential to our every thought and action, and muddying their usage has been central to the traps of circular reasoning and unsound beliefs & practices, which those claiming to be '*those who know best*', have used to lead our society into becoming so lost within, and imprisoned by, our own thinking. And for those who're not sure what I mean by muddying their usage, circular reasoning and unsound beliefs & practices, if nothing strikes you as unsound in "fiery but mostly peaceful protests', or that 'this trans Bud is for you', you really need to stick around for the next few posts, as what we're going to do is focus on how each word can be used to either conceal, or reveal, our world to us. By doing so I think you'll also see why it is that I think that the most important philosophical stands that you and I can take today, have less to do with waging grand public battles against Leviathan, than with consistently making small, often very small points, in daily conversations, so that each of us will see more clearly what it is that is actually being talked about.

IMHO, if 'We The People' are to escape the muddy traps of our public discourse, it'll be as a result of our reclaiming our ability to deliberately engage in taking small, sure, steady steps upon solid metaphysical ground, because that's what has the best chance of bringing about the one thing that truly can defeat the grand Leviathan looming up all around us today - a widespread popular outbreak of sound reasoning, that's primarily concerned with what is real, and true, and right.

Up next: 'What' we are talking about.

Back to Top

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

What the Reality of the Abstract is - 'What is Truth' pt2

The point of turning our attention to metaphysics (see previous post), is not to wrestle with fancy concepts or to see which big brained person said what impressive (or baffling) thing about this or that obscure issue, but so that when we are talking about something as if it is something worthy of our attention, we will have more clarity on whether it actually is something or not, and if so, grasp whether that discussion is taking us towards, or away from, it becoming realized - and is either prospect a good thing?

In proposing to get the hang of this by looking at the three words of:

"What is Truth?", we'll come at the phrase itself last, after first working through the words individually and from an angle, looking less at the word 'What' itself, than with whatever it is that we use it to refer our thinking to.

We of course use 'What' as a placeholder for anything, usually something that hasn't yet been identified, but which the question expects, or at least hopes, will be identified - and while that 'What' can potentially refer to anything, we expect the reply we receive to refer to a particular thing within the context of the question being asked. In short, 'What' is referring to some part of, and by extension to all of, existence itself. That something exists and that we can know that, is the fundamental principle of metaphysics, and leaving a few big-brained fools aside for the moment, few doubt that because it is absurd to question the reality of existence, but it is absurdly common for us to confuse some idea in our heads, with it being real, and seeing how we do that, and how to keep from doing that, is what we're using 'What' for.

If I point at something and ask "What is that?", depending upon the context, the answer received could be anything from applesauce, to a 'bottom operated clapper valve', and while I know enough about applesauce to safely assume many delicious details about it (though depending on who I'd asked that of - waitress or friend or foe - other questions might be asked before taking a bite of it), the other merely names something whose concept means little more to me than the "what" I'd asked of it to begin with, right?

The natural reaction towards the unexpected or unknown, is - demonstrating what Aristotle said that all men desire - to ask more questions in order to make the unknown meaningful enough for it to fit into our understanding. How much is enough, depends upon the context, and fitting some unknowns into your world might not require much at all - if they reply, 'It's something found often on railroad cars', unless I had a deeper interest or need to know about trains, that'd be enough to make this particular "what" real enough in my mind for me to move on to the next squirrel.

But what about when the concept is a familiar one? How often do we assume we know something about what's being discussed, when we actually know little more about the familiar term, than we do of the unfamiliar one?

To get the gist of this, let's imagine a simple example of using a mostly abstract concept, where my wife tells me there's a problem with a room in our house. "What's the problem?" I ask, "it's too dark", she says. "Too dark", I nod. "What we need is a chandelier to brighten the room up" she says, and I nod my head, yep, we need a chandelier.

In this case, the unknown 'What' was filled in by 'chandelier', but annoyingly enough, knowing that we need this general kind of thing called a 'chandelier', though its familiar to me, it hasn't told me enough to even leave the room with, let alone run off to buy one, because although I've got a vague image in my mind of what a chandelier could be, it's no more concretized in my mind than a 'bottom operated clapper valve' is. Far too many of its potential properties are still too abstract in my mind, meaning that - in my mind - they can still hold 'any' value, though you can bet she has a very particular chandelier in her mind, and if I don't want to be left in the dark I need to turn my attention to filling in some of the hazy blanks, such as its price range, or how low it should hang, or whether it should have a simple on/off or dimmer switch, and so on.

The human mind (especially that of conmen) delights in lazily leaving those sorts of abstract details populated with nothing more than our tendency to accept our assumptions as being enough. But for our thoughts to be worth thinking, we need to develop the habit of fleshing those defaults out with questions that direct our attention to filling them in with realistically specific values, or value ranges - concretizing them - in order to identify, to make known to ourselves, the particular 'What' that should be pointed to by the 'what' that we as yet only 'think' we have in mind. Only after doing so can we knowledgeably say "Yes' to this chandelier, and definitely No to those chandeliers, and without doing so, we truly do not know the 'What' that we're talking about.

How appropriately abstract it is for a concept to remain, changes with the context. By that I mean, having no real interest in trains, knowing the 'bottom operated clapper valve' had to do with trains, was all I needed to know about it in that context, whereas in the context of my wife first identifying the solution of a "chandelier", even though the word told us nothing about the many possible details that were as yet entirely abstract in our minds, it was appropriate enough in that context to simply name the concept of a hanging lighting fixture, to distinguish it from all other possible options such as a lamp, skylight, candle, etc.,. But in the context of budgeting and going out to shop for a chandelier requires concretizing it further, even if only generally for issues like price, size, etc., in order to get a clearer understanding of what to look for and where. And yet even that somewhat more concretized status which would be appropriate enough for narrowing the field, would still be inappropriately abstract for the context of my going out to select this or that particular chandelier: what about its material - wood? metal? crystal? - or its shape - round? square? multiple arms? - how about color? size? number of lights?.

Those conceptual details whose concrete values had not yet been shared between our minds (if they were even in my mind at all), not to mention those several other properties that she'd be sure to have in her mind that'd never, ever, cross into my mind, would guarantee that if I were to trot out myself and buy what only seemed to be in my mind, her reaction to what I brought home would be anything but abstract.

To avoid such mishaps, requires our noticing that the same flexibility that enables concepts to be so mentally productive in identifying enough of what we have in mind in a given context (especially in the more specialized fields of science, technology, and literature), is the same feature that makes them so dangerous when we're not sufficiently wary of the abstract nature of the concepts we're using - it's too easy to think (or to give others the impression) that what we have in mind (if anything), is what they do as well. Those abstracts which default differently from one person to another, are what enable those peddling supposedly wise advice, such as the scientistic "...You should only believe a truth that is scientifically verifiable!" assertion, to sound sensible enough to those who habitually think no further upon them than whether or not their sound is pleasing enough to the ear to win their approval. We too easily fail to give those too familiarly used & abused metaphysical concepts the respectful attention they require. Of course the mischief that can result from leaving too many abstract components unpopulated in the concept of a chandelier, are but a pup-tent in comparison to the veritable skyscrapers that metaphysical concepts enable us to carelessly presume we know enough about, and the real world consequences of doing so (such as scientism and Eugenics) can be infinitely worse than confidently buying what you mistakenly thought was the right 'chandelier' at Home Depot.

Developing an attention to metaphysics helps to heighten our conscious awareness of the difference between what is metaphysically real (this physical chandelier), and what is still metaphysically abstract (any chandelier), the abstract is a valuable means for moving towards what's real, but we need to guard against it being mistaken for the real thing. Doing so begins with a conscious awareness of whether our grasp of 'What' + 'Enough' + 'Context' = a calm, or a doubtful state of mind.

One example of a lack of context is the cartoon I've got in the graphic with this post, of two characters standing on either end of a numerical shape and pointing, as one insists '6!' and the other '9!', and the caption invites you to take the relativistic view of 'it's all a matter of perspective', but however useful it is to realize that perspective can influence perceptions, what's more useful is to look for the wider context involved - if the shape is laying on a parking lot, then one end will designate which end is up, and if there is no such context available, then it is only a shape that can be used as either a '6' or a '9', in which case both are wrong for insisting it is one way or the other. That seemingly 'reasonable' path towards relativism is a favorite of modernists (that on the molecular level, a solid is 'akshually!' mostly space is another, more on that in later posts) - reject the ploy and look for the context.

And for those who wish to put feelings and preferences first, there's the other cartoon from the graphic, which shows 'your house' as it's preferred to be seen by you (a nice comfy house), by a buyer (a cheap shack), a lender (an only slightly better shack), and by your tax collector (who prefers to see it as a palace). When you leave too much to the abstract, you lose, bring your ideas into contact with reality, especially question what you assume to be 'true', don't leave your understanding to be defined by feelings and preferences - of theirs or yours - concretize them, or in the end they'll come crashing down on you like a ton of bricks.

Get into the habit of asking a few conscious questions: Does this belong with that?; Is the meaning clear or opaque?; What am I assuming about this from what I've been told, and how much of that was I actually told?; When being advised to do or accept something: Did they provide substance to support their urgency, or did they focus on fanning feelings of peril? Am I being expected to make assumptions about what they didn't say? What reasons do I have to believe that the reality which will follow from this advice, will match up with what they led me to assume about it?

Acting in accordance with reality

Not being so careless as to neglect the metaphysical basics, is a simple, and valuable, habit to learn and acquire, and the good news is that by giving just a little more conscious attention to what those too familiar words of 'is', 'trust', 'should', etc., can provide an otherwise inappropriate cover for, we can eliminate the insubstantial weeds that a careless inattention enables to take root in our minds - especially regarding advice given by 'those who know best'.

How we've come to be so careless and ignorant of metaphysics, is largely due to our schools having pragmatically ensured that we would, and sadly with very little push-back from We The People. If you want to test whether I'm being too harsh or inaccurate, just ask yourself and your friends about what the 'Three Acts of the Mind' are, I'll wait.

Oh... hi again. That was quick.

Were you familiar with it? How many of your friends were? If some recognized the term, how well did they know what it referred to? That's but one of many commonplace fundamentals that 'every school boy' once knew, and the reason why they did, was because familiarity with such concepts was a known means to aiding us in knowing better, what it is that we mean, when we say that something is true.

For those who aren't familiar with the term, here are the three acts that our minds routinely perform:

First Act: Apprehend (Understand) - We open our eyes, and whether seeing something for the first time, or understand that we know it by name, a Rock for instance, we apprehend it, conceptualize, identify itWe aren't ignorant of these terms because they're difficult - the Three Acts of the Mind isn't all that difficult to grasp, some might even rank it on a scale from the simple to complex, as a mere 'duh', but most of us aren't ignorant of the concept because it's difficult to learn, but because our schools deliberately stopped teaching it - I sure as heck didn't learn of it in any of my schools, did you?

Second Act: Judgment - The act of mind which combines or separates two terms by affirmation or denial. 'Rock is hard' is a judgment

Third Act: Reasoning - From our observations and judgments, we move towards further conclusions and applications of them. 'As rocks are hard, I should avoid striking my toe against them.'

(To the Logic folk: Correct, that isn't a syllogism, and Reasoning is not synonymous with Logic - logic is a power tool of reasoning, but that comes much later in the process we're looking at here)

, and from a professor at a Catholic college, Christopher Anadale, who addresses it from a logical point of view: Intro to 3 Acts of the Mind

Lots of other pages can be found on it, such as a study group for C.S. Lewis on the Three Acts of the MInd, and even an Artificial Intelligence enthusiast grasps how vital the Three Acts of the Mind are to actual intelligence, but for videos, only those two.

1st) apprehended what you said,And if they continue to stammer or stare slack-jawed at you, you can ask them why it is that their education has left them ignorant of, or even ridiculing, something which they're now unconsciously employing in everyday life? And do they think that their thinking is more likely to be improved by being ignorant of such matters, or by consciously employing and improving the use of them?

2nd) made a judgment about it, and

3rd) reasoned out a response to it.

So what more can we now know about scientism's advice that: "We should only believe to be true that which can be scientifically proven"?

We can imagine that the image which the phrase expects us to have in mind regarding science being able to provide efficient and reliable answers to us, but we can also see that many important questions and answers which those 'should' (would) apply to, are being left for us (and especially for them) to simply assume, and for everyone to assume that all would go well, without looking any closer at their advice.

If you do give some attention to moving past the abstract defaults by asking some questions, you'll find yourself engaging the Three Acts of the Mind to identify what something is, to understand enough of its nature and purpose, and to reason your way through how such details would and should (and can't and shouldn't) be applied to what, and how, you're understanding of the reality which such unscientifically vague possibilities would entail, and that will likely lead you to so some stark metaphysical clarity about where following such advice might lead you to.

For as you begin reasoning your way through a number of scenarios, you'll surely begin to notice that men in lab-coats are not particularly suited to scientifically examining and testing whether or not you love and believe in your spouse or your children, or whether the issues you care to speak out on are quantifiable or verifiably of value under laboratory conditions (and can you 'scientifically verify' something outside those conditions?). You'll surely also soon discover that other issues such as your own preferences for food and drink and entertainment, are somewhat less than scientifically justifiable, let alone 'scientifically verifiable' (are they even the kinds of values that are 'scientifically identifiable'?), such as what you might choose to read, or what you might think your child's 'education' should entail. You may rest assured though, that the lab-coated ones, who after all, 'do know best' (as they'll authoritatively tell you), will surely have many calculations available, as well as a number of equally 'scientifically verifiable' advisories attached to them, by one committee (soviet?) or another, regarding what they've determined would be best for you, and your family, to do, and what not to do, for the greater good (quantities over qualities!).

Likewise, you'd soon find that they have no ability whatsoever to scientifically test the need or value of your having an individual right to freedom of speech, or whether and what church to attend or if government should establish one (or perhaps a more appropriate alternative) for you, or of the value and need for individuals to petition their government for a redress of grievances, or anything else related to what our Bill of Rights secures for us in the 1st, or any of its other amendments to our Constitution (BTW, is that a 'scientifically verifiable' document? Ummm... no, it's not. Neither, BTW, is 'Justice', hence the addition of 'Social', to transform it into a quantity, rather than a quality).

What you'll see instead, should you dare to apply the metaphysical eye for the Western guy, is that there are plenty of people who're exceedingly happy to don the lab-coat and clipboard garb of scientists, to formulate tests no matter how untestable they might be (which, BTW, is how the 'Teaching Laboratories' in our Teachers Colleges have come up with how to teach what is taught to those who teach you and your kids what not to think about), and they're quite happy to substitute many quantities for any qualities at issue, and then to cite numerous studies so as to tally up very impressive numbers which will be claimed to show that the greater good would be best served by some fraction of, or total and complete infringement upon, one or more or all of those issues of individual rights and property that Western Culture in general, and our Constitution in particular, secure for us.

You'll also find yourself being tut-tutted that 'individual rights' are passe, and that 'Human Rights' are what we... er... 'should'... concern ourselves with today - for the greater good - and that you 'should' be happy with the pleasant efficiencies which they secure for and impose upon you.

How?

"Shhh... don't be a science denier! And stop messing around with such old fashioned ideas as 'Metaphysics'! That's an unscientific subject which you shouldn't believe in!"Get the picture?

The undeniable fact is, that with regard to what we mean by the concepts we use 'What' to refer our attention to, not only does it matter that we have enough clarity in our minds about what we're expected to make judgements upon within our minds, but that what that 'What' designates - the metaphysically real vs the metaphysically abstract - allows or leads us to contextually define, or leave undefined, matters which matter a great deal to our lives.

It's essential to know how we engage with, or else flee from, the reality that is inherent in our consideration of What Is Truth?, and we'll look at the 'Truth' of that, next.

Back to Top

Friday, April 14, 2023

What is Truth: 'it is what it is' or it's 'Turtles: all the way down' - 'What is Truth' pt3

In the previous post we began taking a metaphysical dive into the phrase 'What is Truth?', by beginning with the role that 'What' plays in that - what is being referred to, how well we know it, and how easily we fool ourselves into mistaking what we assume we know, for what we actually know about that what - and it's the role of metaphysics, to keep those unconscious assumptions to a minimum, and the clarity of our thoughts to a maximum. We'll look at what it is that we mean by 'Truth' itself in this post, and then at how 'Is' actively puts 'What' and 'Truth' together in the next post, to see more clearly how our inattention to metaphysics today, has made it so much more difficult to put these three words together in a meaningful manner.

How we determine what is true with some degree of confidence (which should not be mistaken for infallible certainty - that's not an option for the human mind), is more of a question for epistemology, than for metaphysics. Before attempting that, we first need to be more mindful of how it is that these concepts and first principles of metaphysics help us to integrate our ideas, and add clarity to the process of thinking, and how disintegrated, unnecessarily complicated, and confused, even hostile ('That's "your truth", not mine!'), our thinking becomes when we're neglectful of them.

In previous posts concerning the progressive regress of education in America, I've covered a fair amount of the 'Why' behind why we're no longer taught to be mindful of the basics of metaphysics, and it was with his awareness of the causes behind a similar widespread lack of that clarity in his day, that Aristotle wrote of the need for a science of first principles (in his day, 'science' meant only a methodical study, it'd be nearly two thousand years before the term 'science' would break off from the mother-ship of philosophy and become the quantified method of experimentation that it is today), in Book 1, Chp 1, of his Metaphysics, that:

"...And these things, the most universal, are on the whole the hardest for men to know; for they are farthest from the senses. And the most exact of the sciences are those which deal most with first principles; for those which involve fewer principles are more exact than those which involve additional principles, e.g. arithmetic than geometry. But the science which investigates causes is also instructive, in a higher degree, for the people who instruct us are those who tell the causes of each thing..."Being unfamiliar with the metaphysics which Aristotle noted most people were least likely to have a solid understanding of, leaves us with an illusory cushion between our thinking and the gritty details of reality. But as with the 'chandelier' noted previously, those assumptions too easily lead us to behave as if we 'somehow' grasp enough of the details contained within them, when in fact we know more about our assumptions, than the realities which our inattentiveness is shielding us from. On a related note, despite the caricature of moral and virtuous people being cluelessly 'above it all', because true morality and virtue are rooted in sound metaphysics, those who are truly moral and virtuous are far more aware and connected to reality than the supposedly 'hard edged' skeptic ever will or can be. But that's for a later post as well.

Keeping the Western mind more focused on and in touch with what's real and true, was a lot easier when we consciously kept one foot firmly in each of our culture's Greco/Roman - Judeo/Christian foundations, and the first principles which they were formed from. As noted previously, we aren't ignorant of these concepts because they're difficult to grasp, but because they go untaught, and it's because they go untaught, that we're enabled to remain ignorant of their importance in our lives. Fortunately, the concepts themselves are mostly simple - that's why they work - and we only need to develop the habit of attending to what they otherwise keep out of sight, to benefit from them. For instance, there's nothing complicated about Aristotle's simple test for whether or not a fact is true:

“To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true”True or False, it is what it is, right?

OTOH, their simplicity and similarity to other concepts, is where our attention is required in order to make those distinctions between them that inattentiveness otherwise too easily lets slip past us, and equivocation - false equivalents - can introduce small errors that can grow, or be exploited into, larger ones. One such difference that's worth noting, is between what we can see is 'True', and what is meant by 'Truth' - do you see the distinction? We say something is true, as a judgment about a claim, but what Truth is, is what it itself is, which is different from a judgment about it.

Taking up the thread from Aristotle (and Plato), Thomas Aquinas put what it is we mean by what Truth is, as being when our thoughts correspond to what is real:

“Veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus” (Truth is the equation of thing and intellect), meaning that Truth itself is the general quality of our understanding conforming to what is real; and True is that particular judgment which identifies that a particular thing 'is what it is' - if you hold up an orange and say "This is an Orange", I'll acknowledge that this particular judgement of yours is True. As Aquinas put it, restating from Aristotle, that:

"...the judgment is said to be true when it conforms to the external reality. Moreover, the intellect judges about the thing it has apprehended at the moment when it says that something is or is not. This is the role of "the intellect composing and dividing."..."When you give the matter some consideration, it seems obvious enough, but it turns out that this most commonsensical of concepts, is ground zero in the philosophical and spiritual battle we've been engaged in for nearly all of modernity.

So with just a few basic metaphysical principles: that reality exists, that what exists is intelligible, that Truth is our understanding conforming to what is real, and that discovering and acknowledging what is true is of the utmost importance to a life worth living, we have what were and are recognized as being vital by both halves of our Greco-Roman/Judeo-Christian cultural foundations. I'll save the details for later posts, but the first significant shot felt around the world in modernity, was fired upon those foundations by Descartes, with his claim that since reality could always be doubted, the only thing that couldn't be doubted, was whether or not you were in doubt about something within it (or 'it' itself) - meaning... that... rather than Truth being what you have when your thought conforms to reality (and is therefore able to be verified against reality as being true), the new arbiter of 'truths' became whether or not you clearly and distinctly believed that your own thoughts agreed with your own thoughts, and were therefore 'true'.

Through this new doubtful formulation, people soon began imagining that their own thoughts could subdue reality simply by doubting it, as what you don't doubt about what you think, became the 'truth' - 'my truth' - that the remainder of your thoughts should conform to (and of course if some fudging of 'facts' was needed to maintain that conformity, so long as you didn't doubt that it was needed... it was. (Shhh!)). Descartes' blending of pervasive skepticism with strident certainty in his philosophy and 'Method of Doubt', has intrigued Modernity into a labyrinth that soon after began to enclose and imprison us within it, and in a very real sense, only the earlier understanding of Truth can set us free of it.

Not surprisingly, the weapon that the modernist most often uses against what is real and true, is an inexhaustible supply of artificial and causeless doubt. Since Descartes' day, Kant gave the term 'doubt' a more respectable suit of clothes in the form of 'the critical question' (and which Marx much later weaponized as 'subject everything to relentless criticism'), and any reality the modernist desires to be free from respecting (made easier by Kant's declaring we can never really know reality 'as it is'), they simply and endlessly doubt the truth of it, typically by demanding endless 'proofs' of the self-evident.

But what more can be said about Truth, than that it conforms to reality?

Believe it or not, that question is a bit of a metaphysical minefield which you should approach very carefully, because as ideas have consequences, so does engaging with ideas that don't respect the metaphysical guardrails of reality that are meant to keep you on the road to objective truth. The question that should be asked before going down such paths, is not what more can be said about Truth than that it is what conforms to reality, but what would the attempt look like, and should we attempt to say anything more about it, than that?

What would attempting to do so entail? Wouldn't seeking 'something more' require either using some notion that's even more abstract and so further distanced from what is real and true, or by using something... else ... that'd require referencing something that doesn't exist and so is unreal... to verify what is real? Wouldn't you need to know what is real (i.e. self-evidently true), in order to identify what isn't real, in order to use what isn't real, to verify what is really true? Didn't that thought just take our thoughts and spin them around in a circle?!

There are of course some issues that require us to come at them from other perspectives, but a perspective that requires circular thinking and endless regress, will never be one of them. Such practices that lead into self-evidently circular reasoning, will quickly sweep your mind up along with it, but as a general rule, what is even better than exiting such loops, is not entering into them in the first place. A grasp of metaphysics helps us to avoid such traps by identifying their hazards and keeping our attention upon what is real, while exposing what is not true, and cannot be.