How do you bring the clouds down to the ground, without bringing a thick fog along with it? Those higher principles and maxims of law that I sketched in the last post, they've helped define the nature and trajectory of Western thought on law, and the next post is going to have to touch on broader, higher ideals than those... but what do they have to do with our daily lives? How could they have anything to do with your daily struggles to pay the bills, raise the kids right, plan vacations and college, and so on... and on and on and on? Well... not all that much... other than having everything to do with every single bit of every one of those daily concerns.

But who could, would, or will, believe that? Do you?

I'll betcha that when you read "higher principles and maxims of law" a certain mental image came into your mind just at the thought of it. Hold that thought. Hold it, and be aware that many peoples thoughts are full of it. The image I mean. An image, some image, sometimes several images, rather than the thoughts themselves. That's where the fog comes rolling in.

I'd intended to finish this series of posts on the Rule of Law vs its Doppelganger in the Rule of Rules, before Thanksgiving, but I could see that in trying to distinguish between the things as they actually are, and how they are popularly made to appear to be, I couldn't get around taking note of another factor that I'd hoped to leave for later, and that's the mental images which we picture such ideas with, often keep us from actually considering such ideas at all.

For instance, when I say Philosopher, or Roman, Law, John Locke, Founding Fathers...Republic, Democracy, Socialism... there are images that come to mind for you. Such mental images are normal, useful tools of thought, they serve as the icons or captions in our mental Wikipedia, linking to the judgments we've arrived at as a result of thinking things through, making it possible to mention such topics in conversation and proceed on to further thoughts without having to rehash all of the facts and arguments behind them every time a subject comes up; they guide and speed our thinking.

But if you're not careful about what types of mental images you associate with which ideas, or where those images came from, or even whether there is any of your own thinking behind them, the thinking they are useful for, might not be your own.

|

| What's an image selling you? |

Mental images are useful as links or even placeholders, but they are no substitute for information, let alone thinking, yet that is exactly what they are sometimes used in place of. Francis Bacon isn't one of my favorites, but despite differences with the details, I think he would have gotten the difficulty here, particularly with his 'Idols of the Cave', and even moreso with the frustratingly little there is that we can do about it, that is, there's nothing that "We" can do about it, only "I" can.

What you can do about it, begins with noticing the types of mental images you associate with topics - if they take the form of conclusions or ridicule, they tend to divert further thought, rather than encourage it. For instance, the mental image you associate with Socialism might be that of 'Fool!', or 'a threat to a life worth living', or on the other hand 'Ideal!' or 'Making society more fair!'. The first on either hand tends to hurry your thinking along, the second can as well, but they also leave an opening for further thought - 'What makes a life worth living, and how is that a threat?' or 'What is meant by fair, and how does it make society fair?' Either question is useful for further thinking whether you are in favor of or opposed to it, but 'Fool!' and 'Ideal!' guard against any such openings for further thought.

As Bacon said, there's not a lot you can do, but that little bit, drawing your attention to the problem, the failure to question, can help a lot.

Just don't get your hopes up.

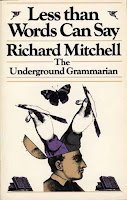

For it turns out that when forming their mental images, many people do accept that a picture is worth a thousand words, not realizing that in doing so they accept all of those words meaning without ever really considering or understanding them, all of which helps us to convey much less than words can say, and then conversation and thought can make no further progress, as your go-to mental image steps in to do your thinking for you.

For it turns out that when forming their mental images, many people do accept that a picture is worth a thousand words, not realizing that in doing so they accept all of those words meaning without ever really considering or understanding them, all of which helps us to convey much less than words can say, and then conversation and thought can make no further progress, as your go-to mental image steps in to do your thinking for you.

This is less a matter of Left and Right, than of being human.

The mental images you associate with Socialism, for instance,

can serve you well, if you've got an adequate knowledge of political philosophy, economics and history behind it - but if you don't... even if the image is 'correct', you don't know it, which means that you've got a deep dark nothing at a structurally critical juncture of your thoughts - how strong or reliable can the rest of your thinking related to that be? And don't we tend to protect those weaker areas of our thoughts, as an animal would their soft underbelly? We tend to snarl and either attack or stalk off, don't we? How does that benefit you or the person you were talking with? If you think of Founding Fathers as Saints, that's better than the opposite, but I've got to question how much understanding you have behind it, and the types of discussions I see that amount to "Liberty! Constitution! I WIN!", don't help the cause of Liberty or increase respect for our Constitution or the Rule of Law.

Put another way, how well can you support the Rule of Law, if you don't understand what threatens it? Hopefully that stirs up an uncomfortable image for you.

Early Images

What kind of mental images are we talking about here? One that first comes to mind for 'big ideas', is that of: useless intellectuals bandying words about in pointless or even dangerous speculations. Admittedly, there's often good reason for that image, and it goes back every bit as far in the West as the roots of the ideas we've been in pursuit of. For instance, everyone recognizes the image of a big thinker walking along, head in the clouds, so wrapped up in his big ideas that he falls into a hole in the ground, right? That image has come down to us from a tale told about Thales of Miletus, credited as the 'Father of Philosophy'. That same image, already old by Socrates' time, was fastened onto him through Aristophanes' play "The Clouds", and with suitably ironic unjustness, in Athenians minds it also put him in the same category with Sophists such as his antithesis, Thrasymachus, it was his advocating for the idea that "Justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger", aka: 'Might Makes Right', made him the veritable Godfather of the Doppelganger, and without which the 'Rule of Rules' would be ruled out altogether.

What kind of mental images are we talking about here? One that first comes to mind for 'big ideas', is that of: useless intellectuals bandying words about in pointless or even dangerous speculations. Admittedly, there's often good reason for that image, and it goes back every bit as far in the West as the roots of the ideas we've been in pursuit of. For instance, everyone recognizes the image of a big thinker walking along, head in the clouds, so wrapped up in his big ideas that he falls into a hole in the ground, right? That image has come down to us from a tale told about Thales of Miletus, credited as the 'Father of Philosophy'. That same image, already old by Socrates' time, was fastened onto him through Aristophanes' play "The Clouds", and with suitably ironic unjustness, in Athenians minds it also put him in the same category with Sophists such as his antithesis, Thrasymachus, it was his advocating for the idea that "Justice is nothing other than the advantage of the stronger", aka: 'Might Makes Right', made him the veritable Godfather of the Doppelganger, and without which the 'Rule of Rules' would be ruled out altogether.

Realizing that such mental imagery is a normal tool of thought, is key to keeping a reasonable control of your thoughts; that and being aware of whether your mental image serves a role in your thought process, or ends the process of thought. The reflexive 'head in the clouds' image is one of those that assigns a fixed judgment to intellectuals, or what we'd call 'Elites' today, and ends - or more accurately escapes - further thought. It also helps you to feel smart, without having to think about the subject at hand; Aristophanes has done it for you. He identified 'big thoughts' as bogus thoughts, and that bogus thoughts led to bad things. Boom, done. Plus, it gets a laugh and encourages the audience to join in on the (three thousand year old) joke with you. Without the habit of reasoning self reflection (which some wish 'critical thinking' could be, but never will), the mental image was established, Aristophanes tagged Socrates as a 'big thinker' for his huge audience, the mental image stuck, and did all the thinking for them.

This was far from simply being an issue of humor, bad PR or media spin, because popular opinion had the force of law - hello Democracy! - Socrates' perceived guilt by association with that image, influenced his trial and execution - so while a picture can be worth a thousand words, it's more than willing to settle on just one: 'Guilty'.

Before you dismiss that as something that happened thousands of years ago, think of today's media, think of the precious snowflakes on our college campuses shrieking their tolerance towards 'repugs', NRA and the Second Amendment, their popularly held image boils down to '2nd Amdt = murderers!'. What mental images do you think that 'they' see when we speak of Individual Rights and the Rule of Law? Do you think that your words are getting past their indoctrinated mental images? Politicians are now playing to that popular opinion by making serious proposals to suspend our rights (and increase their power over us) on the basis of suspicion alone... is the significance of a popular mental image gaining a little more relevance for you now?

Do you have some images that you let do your thinking for you? Are they the right images? How well do you know it? How well can you support that image with words?

Thinking past images

Interestingly, those derisive images of elite big thinkers and big thoughts, popular with Athenians then, and Americans now, doesn't gel with the images held by those who would become our first Americans at the time of this nation's founding. Somehow or other during that period, from farmers to philosophers, 'big thinkers and big ideas' were seen as being both important and practical. During that period, which lasted for somewhat over a century for English speakers on both sides of the Atlantic (moreso on our side), the relationships between Big Ideas and Little Realities were strengthened, clarified, and came remarkably close to being seen as the common knowledge for the 'common man'.

There's another 'big thinker' mental image of that same Thales of Miletus, that was more fitting to their time, that comes down to us via Aristotle, with Thales' response to being mocked for his lack of wealth:

"When they reproached him because of his poverty, as though philosophy were no use, it is said that, having observed through his study of the heavenly bodies that there would be a large olive crop, he raised a little capital while it was still winter, and paid deposits on all the olive presses in Miletus and Chios, hiring them cheaply because no one bid against him. When the appropriate time came there was a sudden rush of requests for the presses; he then hired them out on his own terms and so made a large profit, thus demonstrating that it is easy for philosophers to be rich, if they wish, but that it is not in this that they are interested."That image of a moral and effective thinker actually applying big ideas to improving their standing in the community and turning a profit at the same time, was more in keeping with the thinking of the typical farmer in the street, during that period when the West's elite weren't simply assumed to be mouthing arbitrary noodlings floating about in the clouds, but instead were understood to have a connection to the real world, to be of interest, having tangible, profitable applications and benefits for everyday life and the quality and depth of that life, here and now.

How alien does that feel?

Here's the important point: While also a mental image, the nature of that image directs a person's attention to Questions and Purposes (How did he know about the weather? How'd he connect weather, olive presses and wealth together? How can I do something like that?). Those kinds of images encourage thoughtfulness and discussion, rather than to presume conclusions and divert attention with Mockery and Derision (Ha! He looks like the kind of fool that falls into a hole, doesn't he!), and ending consideration altogether.

But to move beyond thinking with images to thinking with words, you've got to have actual ideas, principles and a valid organization of words and concepts you understand, to move beyond them with, or at least a desire and willingness to go and get them.Which image do you think encourages that most, derisive laughter, or purposeful questioning?

A Common Wealth of Ideas

You can get a sense of how different our mental images are today, and what they aren't backed up with, from the more common ones held then, from a letter that Jefferson wrote to a friend in later years, recounting what the Declaration of Independence was meant to accomplish:

"Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c..."[emphasis mine]Take special note of that last phrase "the elementary books of public right", that was not a reference to those with "their heads in the clouds", nor to anything like our 'daring' college professors preaching 'new', 'revolutionary' ideas (like freedom from speech) from secure chairs in their ivory towers... no, no, no, far from it. Rather than scribbling down all of his super-dee-duper-inspirational ideals to start a revolution with, Jefferson instead took it as his charge to put the ideas already widely held in the colonies, into a short, catchy, declaration which nearly everyone walking down the street, on seeing it tacked onto a post in the town square, would read it, understand it, nod, and be inspired from the bottom up to move forward together with it.

Those common ideas Jefferson was referring to, were instilled from the cradle on through nursery rhymes, fables, epic poetry and historical tales; they were known, discussed and haggled over, over at the neighborhood pub. Understand, I'm not claiming that every blacksmith and farmer was, or cared to be, an intellectual, but not having the time or inclination to delve into a subject with the depth that an intellectual would, didn't mean that the average person wouldn't familiarize himself with those matters; those 'expressions of the American mind' were familiar topics of discussion for the rich and poor and were rooted in the soil of the ideas of 'Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney', in a list that also included Aesop, Virgil, Plutarch and Shakespeare & Homer and the Bible... and more. Just how much more can be glimpsed from a request made by Jefferson's future brother in law, Robert Skipworth, in 1771, for his recommendation for a list of books for his own benefit,

Those common ideas Jefferson was referring to, were instilled from the cradle on through nursery rhymes, fables, epic poetry and historical tales; they were known, discussed and haggled over, over at the neighborhood pub. Understand, I'm not claiming that every blacksmith and farmer was, or cared to be, an intellectual, but not having the time or inclination to delve into a subject with the depth that an intellectual would, didn't mean that the average person wouldn't familiarize himself with those matters; those 'expressions of the American mind' were familiar topics of discussion for the rich and poor and were rooted in the soil of the ideas of 'Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney', in a list that also included Aesop, Virgil, Plutarch and Shakespeare & Homer and the Bible... and more. Just how much more can be glimpsed from a request made by Jefferson's future brother in law, Robert Skipworth, in 1771, for his recommendation for a list of books for his own benefit,

coffee and ale

"...I would have them suited to the capacity of a common reader who understands but little of the classicks and who has not leisure for any intricate or tedious study. Let them be improving as well as amusing..."The list that Jefferson suggested for the benefit of a common reader to use, would put to shame the resume that typical college professors use as a claim on public funds. But before looking at Jefferson's reply, there are two points that are vitally important to grasp here:

One, is that those ideas that were so common to them, for common interest and entertainment, involved the reader in (Jefferson's spelling and terms) "Fine Arts, Criticism on the Fine Arts, Politicks, Trade, Religion, Law, History-Antient, History-Modern, Natural Philosophy-Natural History, Miscellaneous."Skipworth understood that he wasn't an Elite as his future Brother in Law was, but neither did he see that as somehow separating their common interests.

Two, is that Skipworth was seeking that list of books to improve his own education, his own understanding, for his own betterment, NOT in order to make himself more economically marketable to other people, and yet, he was also doing so without either denigrating the idea of making himself more economically marketable, or of thinking that the two were somehow in conflict with each other!

Now, how alien does that feel?

The Real Aliens

Now let me ask you to ask yourself, what reaction do you notice yourself feeling towards Jefferson's list of topics? Is there an image that pops up in your mind? Take another look, his list of topics, in current terminology:

Art, Aesthetics, Literature, Political Philosophy, Economics, Religion, Law, History, Science, Metaphysics, Ethics.And if we add Virtue (which was the point of them all) to the list? Tell yourself truthfully, are the images that come to mind, those of quietude, respect and reverence, or louder ones of dismissiveness and ridicule? Something like Rodan's 'The Thinker', or more Bart Simpson & Southpark? Maybe with a Jon Stewart-ish smirk? Or maybe they seem "okay" but too distant, like peaks on some distant mountain that you'd like to someday, sometime, maybe get around to climbing?

Both views, that elite or big thoughts are too silly, or too distant, to matter to your life, are heads and tails of the same coin, an explicit, or implicit, denial of reality and the ridicule of truth and virtue (can't have one without the other). As that has been taught more and more openly over the last century, it's what pops up in the backs of nearly everyone's minds today, but it's a view that by its own admission is based not on knowledge, but emotions, and derisive ones at that. There's almost a poetic justice involved, as this is Aristophanes' joke now turned around upon the audience, they are now the ones with their heads in the clouds.

A key difference between our Founders era and ours was that they were more deliberate in thinking for themselves, they weren't turned away from a world of ideas by an inner twitch - they looked. They questioned. If something had value, interest and utility in their everyday lives, it was welcomed, and if it undermined or threatened those, it was rejected, and being familiar with the principles involved, the relevance and benefit of those ideas to their everyday lives was more easily seen.

If you choose to steer, rather than to be steered, you can see the ideas in the world, and the world itself as it is and actually could be. We don't need to change the world, only to enhance our awareness of it. Such a mind has as much room for Shakespeare's plays, popular mechanics, gardening, sports and atmospheric measurements. That too could be glimpsed in the numbers of colonists who took daily meteorological measurements, and in Ben Franklin's Pot Belly Stove, as Jefferson's eagerness to design an improved plow showed that,

"He brought his love of mathematics to his design, which he declared was "mathematically demonstrated to be perfect.""Franklin and Jefferson were, of course, famous for their innovations and inventions, but those were focused reflections of those ideas their fellow Americans had in common, and similar small scale actions were taking place all across the land by the intellectual and the common farmer alike, and though the latter might not be as involved, less involved should not be thought to indicate that they were ignorant of, or unfamiliar, with those big ideas we've been speaking of. Keep in mind, the Federalist Papers were written, for the most part, with the common 'farmer in the street' in mind - they were its target audience!

How? Recall the suggested reading list that Jefferson replied to his future brother in law as being what a common man would enjoy and should benefit from, "...I have framed such a general collection as I think you would wish, and might in time find convenient, to procure..." , but this passage on how such works become not only pleasant, but useful, is key to restoring the best images to our thoughts:

"... A little attention however to the nature of the human mind evinces that the entertainments of fiction are useful as well as pleasant. That they are pleasant when well written, every person feels who reads. But wherein is it's utility, asks the reverend sage, big with the notion that nothing can be useful but the learned lumber of Greek and Roman reading with which his head is stored? I answer, every thing is useful which contributes to fix us in the principles and practice of virtue. When any signal act of charity or of gratitude, for instance, is presented either to our sight or imagination, we are deeply impressed with it's beauty and feel a strong desire in ourselves of doing charitable and grateful acts also. On the contrary when we see or read of any atrocious deed, we are disgusted with it's deformity and conceive an abhorrence of vice. Now every emotion of this kind is an exercise of our virtuous dispositions; and dispositions of the mind, like limbs of the body, acquire strength by exercise. But exercise produces habit; and in the instance of which we speak, the exercise being of the moral feelings, produces a habit of thinking and acting virtuously. We never reflect whether the story we read be truth or fiction. If the painting be lively, and a tolerable picture of nature, we are thrown into a reverie, from which if we awaken it is the fault of the writer. I appeal to every reader of feeling and sentiment whether the fictitious murther of Duncan by Macbeth in Shakespeare does not excite in him as great horror of villainy, as the real one of Henry IV by Ravaillac as related by Davila?..."Something important that Jefferson notes here, is that it's not the West that makes the works important, but the works that made the West, and the works had that power because of the questions and responses they evoke, and we rightly value some of those more than others because they do that so well - but they aren't the only ones that can. This might surprise you, but no matter how enthusiastic I am for history and literature and philosophy, they aren't the answer. Sure, they help deepen your understanding, and yes, Aristotle, Cicero & Locke are necessary to an understanding of the Rule of Law, but the answer that matters is that you understand that reality is real, and that you can know it, and that it is true that what you do matters. It's about what those works can do to us, that makes them so valuable, the mental images they help us paint and then guide us by, not who wrote them, or how famous their titles are. It's as foolish to turn from them because of their association with the West, or with foolish elites, or the mental image of being useless ideas, as foolish as it would be to ignore gravity because of who first grasped and wrote of it.

Understand that, and all the rest can and will follow. Deny that, and you alienate yourself from living in liberty. Understanding and acting on that, places you within The West. Denying, ridiculing or attacking that, makes the West in general, and America in particular, into an alien culture to you - it puts you at war with it, and with yourself.

There is no path that leads towards real progress, towards a realization of Justice and Tranquility and a life worth living, which isn't either barred or opened up, by the mental images we mark those paths of our thoughts by - and if those images don't invite thought, they might as well read "Bridge Out". There is no coming to a defense of Individual Rights under a Rule of Law, except through the expectation that what IS, is important to what Should be - and yes, an IS does imply an Ought (oh, did an image just pop up in your mind? Ask yourself: is it encouraging you to think or to turn away from it?), or as our Declaration of Independence states it: ' to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them' that is what that means.

If you don't believe me, just ask President Obama, or Bill & Hillary Clinton, or Bernie Sanders, they'll absolutely agree that I'm wrong.

Do you get the picture? Are you asking why?

America and The West are not about 'the answers', they are about the Questions we are willing to ask. And I do mean Questioning, not Doubting! Easy 'Doubts' encourage those empty images that form intellectual cavities and Truth Decay. The rest follows. But what it follows from, is asking a question and knowing that answers are possible and worth pursuing, if you pursue them honestly and methodically, and that respect for reality is the precondition for knowledge and an Education worthy of the name. If you don't have that, whatever degrees you might acquire, whatever images you puff yourself up in association with them, are truly meaningless, as are their, and your, relevance to our lives.

That's enough. It is not our task or within our power to change another's mind - and if somehow we were able to, they'd likely be changed again with the next verbal wind to blow through - simply seek to engage them, lead them to ask questions too. Raise the image that Ideas and Reality are not in opposition, and that harmony and happiness is what follows from realizing that. If you can get yourself and/or them to wonder if that could be true, and if so, how, that's all it takes.

Ok, next post, images aside, it's back to the question of how the Rule of Law follows from those big ideas fastening into our lives through the everyday facts of living, and we'll begin looking at that process in the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment